“The size of your dreams must always exceed your current capacity to achieve them. If your dreams do not scare you, they are not big enough.”

― Ellen Johnson Sirleaf

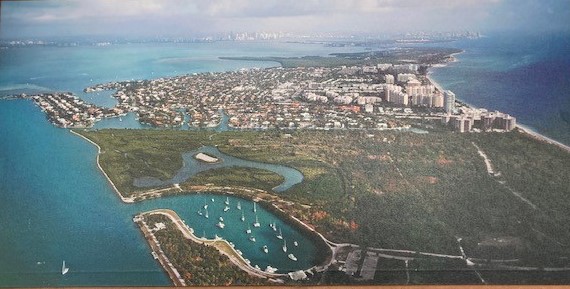

Sitting in No Name Harbor, we contemplated our options. The good news: we were safely at anchor, we didn’t have a schedule to keep, and we had plenty of food. The neighbors in the anchorage were polite, for the most part, and kept their music soft. Some nights, there were only two boats anchored, but on Saturday night, there were many. We kept cool by swimming and running the air conditioning by generator for an hour or two before bed. The bad news: we had an engine that spewed white smoke and wouldn’t power up past 2,000rpm.

It was scary to think of continuing our trip without solving the problem. We could be anchored off Rodriguez Key with no engine, no wind, and no way to get towed to our destination without spending thousands of dollars. We were out of options until a friend called with a suggestion, and an offer.

“I can join you onboard and help limp the boat to Marathon in one overnight passage,” Reinhard said. “We can sail if there’s wind, and just motor slowly if not.”

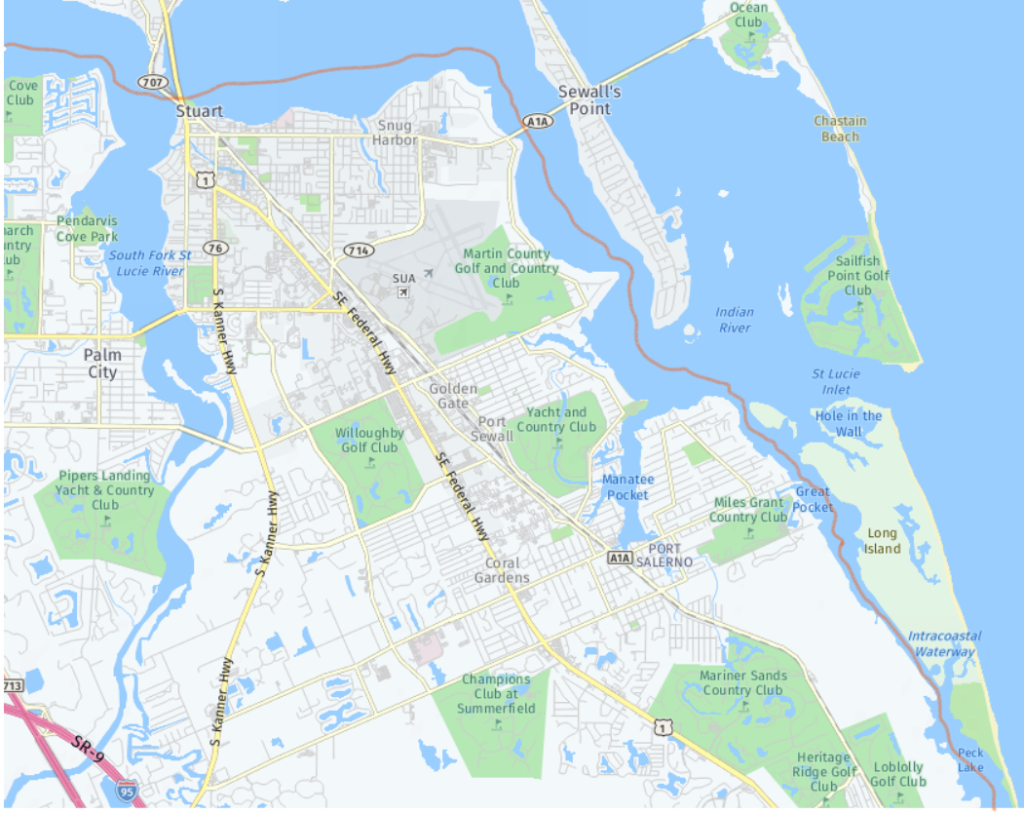

Phil and I had never sailed at night, and it was not something we planned to do in the near future. To be honest, we had precious few working flashlights, no spotlight, and the compass light did not work. We also had some doubts about the auto pilot. Our running lights worked fine, and if we were able to maintain a speed of four knots, the 90-nautical-mile passage would take just short of 24 hours. At the end of that journey, we would be in a place where sailboats were more common than power boats, and diesel mechanics might be available. There is also a travel-lift and a boatyard right at the marina. Plus, we would be home. We said yes, and planned to leave on an outgoing tide Monday at noon.

I discovered a free transportation service called Freebee in a blog posted about No Name Harbor, and downloaded the app. We requested a ride to the Wynn Dixie store a mile or two away and went to the wall in our dinghy with our grocery bags. It was amazing! The electric vehicle came quickly, the driver was helpful in every way, and we were able to replenish our drinks and some small food items. Normally against our principles because of the plastic waste, we even bought a case of bottled water since our tanks were a little low. (There is no public drinking water at No Name Harbor.) The return driver even helped us carry the water to our dinghy.

Monday came, our guest arrived with his wife Nina, and after brief goodbyes, we cast our lines off at 11:40 am heading out of the harbor. It was hot, still, and flat calm – a mixed blessing.

We turned to the southwest and saw a disturbing sight: the wreck of a green navigational beacon. We hoped the others marking our way through shallow passages were in better shape, especially those we had to pass in the dark. We really wanted to sail, to help the engine a little and practice our skills with an expert on board. But the wind was directly on our nose, so no chance of forward movement with that angle. We motored, watching whisps of white smoke flow off the stern.

Reinhard discovered the auto pilot was broken but not dead. It could be repaired, once we were able to take things apart and put them back together. So, we had to hand-steer for 90 nautical miles, taking turns at the wheel. Phil had expected to stay up all night, but I thought we could nap in turns. I had underestimated my ability to stay awake, and I did the most napping. During the day, we all took turns steering, but once darkness fell, I took the helm just once. It was too dark and dangerous to rely on my poor night vision and limited skill level.

As we gradually changed our course from southwest to west, the wind also changed. It was definitely taunting us, keeping our sails furled and useless. We could sail by heading off course and then tacking back, but it’s a slow way to go. The plus side was the complete lack of waves. It was quite flat. In fact, the battery died in my motion-sickness band, and I didn’t even notice.

By late afternoon, we had passed some familiar landmarks. We spotted the Boca Chita light – where we had anchored the night Fidel Castro died (another story, another boat). Elliott Key’s long shoreline gave way to Key Largo, where Phil saw the Fowey Rocks Light – a favorite snorkeling spot opposite John Pennekamp State Park. We passed the first anchorage we had planned to use on the way down, Rodriguez Key, and I whispered a “see you later, sometime” as we passed it by.

We started to feel a little whisper of wind, and got our hopes up, but the direction kept changing. It turned out we were alongside a small weather system, and rain appeared in a gray curtain to our starboard side. We watched it get closer, but it never really reached us except for a few fat drops that made plopping sounds on the bimini above us.

The sun started dropping into the clouds above the storm, and we kept trading places at the wheel. There were snacks of bagels and cream cheese along with a large jar of peanuts, but no dinner. The voyage started to feel long, and the hours crawled by as I noted our progress on the paper chart. If you ever think of this planet as a small world, consider how long it takes to go just 90 nautical miles by sailboat.

The chart plotter kept track of our expected arrival time at the marina, and it looked for a time like we might arrive before first light. Luckily, currents kept us back a little and it looked like we would arrive just past daybreak. The sky became inky black with a miraculous display of stars. It was a little cooler, and Phil and Reinhard took turns at the wheel while I stared at the sky. Objects in the total darkness were hard to make out, and there were navigational beacons with no lights marking shallow spots. This is terrifying, and we passed close enough to one marker to make out its hulking shape in the shadows off to our port side.

Boats with improper lighting gave us a few mysteries to solve. Off in the distance we saw a white anchor light and two fainter red and green running lights. When we got closer, we realized it was a catamaran anchored two miles offshore with a dinghy attached to stern davits. The lights were glowing on the dinghy, creating a strange configuration in the dark. Another mystery was a steaming light above a set of brighter spotlights and no running lights. It looked like a huge ship on the horizon but turned out to be a small-powerboat captain trying to repair his engine under his bright deck lights. He was anchored, it was the middle of the night, and he had our sympathy.

First light saw us alongside Key Marathon, and we made a slow turn toward land. I could see the headlights of cars on the Seven Mile Bridge, and the one green marker with a 4-second light. Four seconds seemed too long, and we knew if we got out of the narrow channel, the water was only three or four feet deep.

Eighteen and a half hours into our trip, we made the turn into Boot Key Harbor as the sun came up, and Phil steered us slowly along the row of boats to our spot on the west dock. Reinhard stepped off the boat onto our pier, and tied up Catmandu in her new home, slip 98, Safe Harbor Marathon.

Safe Harbor – There are few nicer phrases after a long passage in the dark.

Loved this and learned a lot! Since I don’t see well from a distance, identifying birds has always been a…

Lovely writing, Kay! Engaging and evocative.

[…] My favorites are the pelicans. They are huge, with brown bodies and white heads folded down into their necks.…

loved reading this. i felt like i was there. and u both are nuts!

Yippee! A great read from Ms Kay. Almost felt like I was there. Of course, the best thing would be…