“You’ve lost that SQUEEZING feeling!”

I shared this insight with some other boat owners, and they all agreed that, definitely, putting your boat into the water is asking for trouble.

— Dave Barry

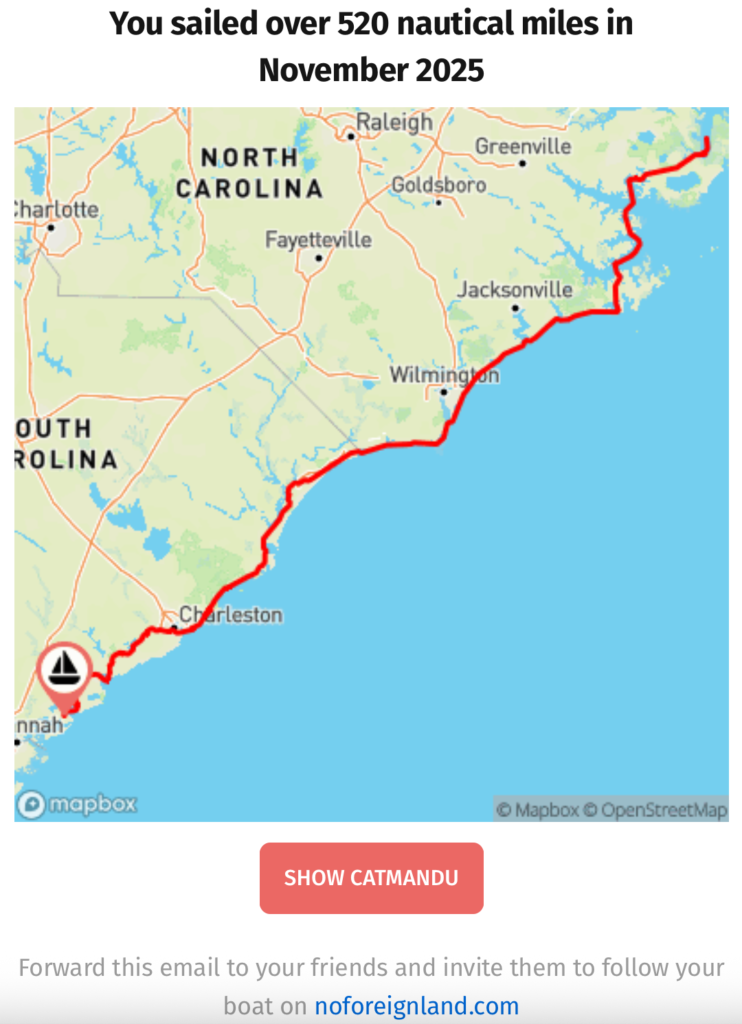

Catmandu does not have an engine anymore. The 27 year-old diesel engine on our Catalina 380 monohull sailboat is gone. After motoring and motor-sailing for several weeks south from Annapolis on the Atlantic Intracoastal Waterway, Kay and I are stuck at a marina only halfway on our thousand-mile plus journey from Annapolis to South Florida.

The last several weeks of our journey have had their share of not-so-great surprises (warships, murder barges, and cold weather), and some great surprises (bald eagles, fall colors, and dolphin sightings almost every day). Traveling the same stretch of water a second time this year brings a familiarity and comfort that makes the journey more fun. Since we have been keeping a daily cruising log, we can easily recall where we went before and avoid the marinas and anchorages that were not five-star stops. We can also revisit the five-star stops and try out some new marinas and anchorages. Finding new places is also fun.

When I was a young engineer working for Westinghouse in the nuclear industry in the 1980s, I learned the importance of backup systems and avoiding a single point of failure. For example, our sailboat batteries can be charged by shore power, the engine, and solar panels independently. A sailboat always has both sails and an engine, to be sure. On the ICW, however, one can seldom sail in the narrow, winding channels. That means there is no replacement for the engine, which is a single point of failure.

Our Westerbeke 42B Four was slow to start as we were leaving Annapolis in late October. It was in the 40s Fahrenheit. The engine would crank for a half a minute or more before turning over. This had never happened in our six years of ownership, but we had never operated the engine in such cold weather. I just chalked it up to the cold, and went onward. Maryland, Virginia, North Carolina, and then South Carolina. The hesitation became worse and worse with each passing day, but the engine always started eventually.

At Hilton Head Island, South Carolina, we took a slip at Safe Harbor Skull Creek Marina, as we had in July on our way north. We intended to stay for only one night. However, the next morning, the engine simply would … not … start.

Diesel engines are “simple” in that they need only air, fuel, and compression to run. I went through the entire troubleshooting charts from the engine operator’s manual and Nigel Calder’s Marine Diesel Engines reference book. I checked the fuel cut-off lever, changed the fuel filters, checked for blockage in the air intake manifold, opened the fuel tank to check for water and debris, removed and inspected the fuel pick up tube, tested the glow plugs, and checked the fuel lift pump. No joy. As Nigel Calder says, if you have done all of these things and the engine still does not start, “it is time to feel nervous and check the bank balance.“1

We called in a mechanic, and days later a man looking and talking like Nick Offerman showed up at Catmandu. He went through the whole system and found that — even without a compression test — the engine had little compression and there was significant piston blow-by. Internal combustion engines work by the principle of suck, squeeze, bang, blow. Air and fuel are sucked into the cylinders, they are squeezed by pistons, they are ignited with a bang, and then the exhaust gases are blown out. “Honey, we are out of squeeze,” I told Kay.

The mechanic said the piston rings are probably bad. The rings maintain compression in the top of the cylinders and keep the oil in the crankcase below. If the rings are bad, there is no compression and the engine will not start. New rings are not terribly expensive, but the bad news is that replacing them requires taking the whole engine out of the boat and disassembling it to be able to remove the pistons and the rings.

Our mechanic and his helper unbolted the engine and hoisted it to the dock under the boom (dot com) and took it to their shop. Not only were the rings bad, but the cylinder walls were scored and worn, pistons had erosion, the cam shaft had a worn lobe, and the crank shaft had deep scoring at the oil seal. Mr. Offerman (not his real name) kindly did the research but found that not all of the necessary replacement parts could be sourced. It was time to buy a new engine.

Westerbeke no longer makes engines for the domestic market. What kind of engine will Phil and Kay get? When will it arrive? How will it be installed? When can Phil and Kay resume their journey “home,” wherever that is? Stay tuned for our next episode.

- Calder, Nigel, “Marine Diesel Engines, Third Edition,” McGraw-Hill 2007, p. 105. ↩︎

An Eagle, a Warship, and a Murder Barge

Right of way: Nautical legal principle that establishes whether or not a particular boat

has the right to ram or the duty to dodge in any given marine encounter.

“Ahoy” is the first in a series of four-letter words commonly exchanged

by skippers as their boats approach one another.

— Sailing, by H. Beard and R. McKie“Schmidt!”

— Phil Decker, S/V Catmandu

Leaving Annapolis

As we made our way out of the crowded fairway of Back Creek, Phil noticed a large bird flying solo over the harbor. “Could that be a bald eagle?” he asked.

“No, I think it’s too small,” I said. Just then, it landed on the green channel marker next to us, its large white head gleaming in the early sunshine. It perched there, looking like a sculpture – like the symbol of freedom it is, and I admitted I was wrong. “Oh, yes,” I said, “That’s an eagle.”

“A good omen,” said Phil.

We turned into the wind and raised the mainsail. So it began, the best day of sailing either of us can remember. We were headed to warmer weather, but first, a clear cold day with perfect wind and sea conditions made us wish we could stay longer and sail around the Chesapeake. We unfurled the jib and headed southeast with a 10-knot wind from the northwest. Within ten minutes, the engine was silent and Catmandu was flying over the water, reaching speeds of 8.6 knots in favorable current. We were thrilled.

When we reached Solomon’s Island, we pulled into the mooring field and searched for our reserved mooring ball. When we found it, Phil rushed up to the bow and I steered Catmandu so Phil could reach the pennant. He got it, first try, and we were celebrating in the cockpit moments later. A blue sailboat with red canvas (S/V Red Shift) came in next and maneuvered around the other sailboats in the mooring field. A woman stood on the bow and shouted into the wind:

“So many sailboats! I have found my people!”

We laughed and waved. Phil and I have felt this way in Annapolis, in Marathon, and recently on the ICW. The Intracoastal Waterway is now crowded with sailboats heading south, politely asking each other on the VHF if it’s okay to pass. We have found our people. (Now we follow Red Shift on No Foreign Land, an app that tracks the locations and voyages of member boats, and they follow us.)

Phil was up at dawn and checked the temperature in the cabin. It was a chilly 55 degrees. We bundled up and motored out into a rolly Chesapeake, heading to Deltaville. We anticipated a 10-hour day, but with calm seas, a sail up, and a clean bottom, we arrived in 8-1/2. We had been to the Regatta Point Marina last August, and the dockmaster Don remembered us. Being plugged in to the dock meant we had heat overnight. The next morning, Don helped us out of our slip. It was a tight turn into the fairway, and we ended up with our anchor clanging into a piling behind the boat in the next slip. With me pushing against the piling, and Don’s help at the dock, Phil got the boat straightened out and we were on our way.

In mid-afternoon, just barely into the Norfolk inlet, Phil spotted a dolphin crossing in front of Catmandu. I looked up to see two more. We had not seen dolphins this far north before. As we made a right turn toward our anchorage at Fort Monroe, a majestic wooden schooner named Godspeed appeared on our starboard side. They called on VHF asking if they could cross our bow and pass port-to-port. We slowed down and let the stately sailing ship pass.

Getting Through Norfolk

Catmandu spent a quiet, cold night anchored at Fort Monroe / Mill Creek (in the company of 19 other boats) and left very early to start into Norfolk Harbor. As we motored into the busy channel, a gigantic cargo ship bore down on us from the port side, and an equally enormous ship had just crossed our bow. The cargo ship gave five blasts of its horn (the “danger” signal) and just as I asked, “Was that for us?”, they radioed us by name, saying we should “stand clear.” Those ships can take up to two miles to come to a stop, and do not turn on a dime. We were only too happy to stand clear and let them pass.

We pulled into a line of boats heading west into the port of Norfolk, hearing the constant scoldings on VHF telling captains to “Slow down! This is a no-wake zone.” Behind us, a huge Navy ship was gaining on us, forcing us to slide to the right. Phil was at the wheel, watching the port side of the channel and I was watching the encroaching Navy vessel.

“Schmidt!” Phil yelled, and suddenly our boat veered to port. I looked at Phil to see if he was okay and immediately saw the problem: a fuel barge the size of a football field was being pushed into the right side of our boat, barely 200 feet away and closing fast. The tug pushing it was not about to change course (sailboats be damned) and Phil spun Catmandu in a tight circle to the left to avoid being hit. The tugboat, the Potomac, did not call us, did not veer off, and continued as if we were not there. Only the quick action of Phil behind the wheel kept us from being pulverized.

“Schmidt?” I said, after we regained our course and our composure.

“Well, it’s not what I wanted to say,” he admitted.

“Did you get the name of the murder barge?” I asked, coining a phrase that felt appropriate.

“I got the name of the tug – Potomac,” he said. “It will go in the log.”

On to Great Bridge

At the southern end of the busy Norfolk port is a lock and bridge that lead into the ICW. The bridge has been under construction for some time, and currently opens only on the even hours between 8 a.m. and 4 p.m. The lock, a half mile away, opens in concert with the bridge. In order to make the 2 p.m. bridge, we had to be at the lock by 12:30.

Avoiding cargo ships and murder barges proved difficult but we made our way with other boats our size and soon put most of the busy Monday morning traffic behind us. Ahead of us, we saw a large Navy vessel with “29” painted on the side. There were around five tugboats hanging around and we attempted to pass the warship to the right. A sailboat in front of us slowed down and so did we. Not sure what to do, we circled behind the sailboat and waited for the tugs to do something. Several other sailboats caught up and we paraded in a circle, looking like a slow regatta. Soon no one could fit through the channel.

Finally, the radio squawked. “All vessels, all vessels, Warship 29!”

Warship 29 is the USS Beloit, a littoral combat ship. “We will be exiting the slip and occupying the entire turning basin. All vessels are advised to stand clear.” Since we were circling in what appeared to be the turning basin, we wondered where we were supposed to go. Soon it was made clear that we were expected to backtrack and tuck out of the way while the behemoth backed slowly into the channel, aided by tugs, and turn completely around. The sailboat parade headed back where they had come from and waited.

A full thirty minutes later, we were still waiting for the “all clear” when the boat in front proceeded to enter the basin again. We followed, afraid the long delay would make us miss the lock and bridge. The Navy ship was nearly turned around when we slipped past it and headed for the Gilmerton Bridge, along with our sailboat parade. After the bridge, most of the other boats stayed to the right to enter the Dismal Swamp. Our draft, at five and a half feet, is too deep for that route. Besides, who wants to enter the “Dismal Swamp”? The name alone steers us elsewhere.

We kept going and entered the Great Bridge lock on schedule at 12:30 p.m. We were the third boat to pull in, but we waited over an hour for five more boats to enter. As we waited, a graceful little baby deer ran through the lawn next to the lock and bounded into the forest beyond. It was too quick for a picture. It was adorable.

Gales were predicted for the next few nights, and we had no desire to anchor out or cross Albemarle Sound in that kind of wind. A gale is defined as sustained winds between 34 and 47 knots. We docked easily at Atlantic Yacht Basin and spent three rainy days and nights in our cozy boat, tied securely to the sturdy dock, far removed from megaships, murder barges and the U.S. Navy.

Going Home, Again

“Let your home be your mast and not your anchor.”

— Khalil Gibran

“‘Home’ is any four walls that enclose the right person.”

— Helen Rowland

“You Can’t Go Home Again”

— 1940 novel by Thomas Wolfe

Fleeing Summer Up the ICW

We left Hollywood Florida in mid-June when temperatures and humidity make outside living unbearable. Phil and I wanted a more temperate summer, where air temperatures drop at night and we could enjoy cocktails in the cockpit without roasting. Many “snowbirds” travel between homes in New England and Florida, but few take their homes with them.

It was late in the season to start up the ICW, and we knew it would be hot well into North Carolina. Our boat has air conditioning, but only if we are plugged in to a dock. We can also run A/C on the generator when we’re at anchor, but that can be annoying to others in the anchorage and makes it hard to sleep.

I took a week off to visit my sons and grandson in New Hampshire, leaving Phil at Titusville Marina where he could monitor rocket launches from the boat. So, we didn’t really get started until mid-July. We spent time with close friends in Melbourne, and four days in St. Augustine – one of our favorite ports – as I waited for shipment of a cancer drug I needed. Our amazing and generous friends there loaned us a car so we could pick up the package at St. Brendan’s Isle, an address cruisers know well.

The slow passage through “the ditch,” as the ICW is called, took weeks. It was hot, but the waterway winding through the wilderness in Georgia and the Carolinas is stunning, revealing a landscape so remote our own anchor light was the only light we saw after darkness fell. Stars blazed overhead at night, the bright Milky Way a smear of starlight across the dark canopy.

We were greeted by dolphins in anchorages so far from the ocean we wondered how in the world they got there. We saw egrets, ospreys and roseate spoonbills along the way, and noisy flocks of Canada geese. The spoonbills are lovely, pale pink and white like flowers. They do a strange dance when feeding, swaying their heads back and forth in the shallow water.

There were tall white shorebirds that could be Great Egrets or Great Blue Herons in white phase. (You have to see their leg color to tell the difference.) Dolphins seemed to swim with us unseen, just popping above the surface to delight us now and then at sunrise or just as we were dropping the anchor. Sometimes they had little ones with them, just two or three feet long.

Catmandu cruised through the quiet and lovely Waccamaw River, reminding me of Kipling’s “great gray-green greasy Limpopo River, all set about with fever trees.1” We didn’t love Morehead City Yacht Basin, but it was quiet compared to Mile Hammock anchorage, where giant military Osprey helicopters took off and landed in a deafening roar every ten minutes until midnight, looking like giant angry grasshoppers. The next day the calm of Adams Creek made up for it. We stopped at Oriental Inn and Marina, and made an appearance on their Facebook page.

Going north through the lock at Great Bridge, we were one of only three boats and planted a Catmandu sticker on the bumper piling. With ICW Mile 0 behind us, we headed through Norfolk listening to one very loud man on the radio yelling at boaters to slow down in the no wake zone. Weather turned windy and rainy at the mouth of the Chesapeake, pinning us in Deltaville for three days.

At Home in Annapolis

We arrived in Annapolis near the end of August. It was unusually cool. We had been wearing our sweatshirts since North Carolina and loved the fall in the air. Good friends from Fort Lauderdale took us to the airport the next day so we could fly down to retrieve our car and return with it on the Autotrain, an experience that deserves its own blog. Then, a week later, we were flying to Greece for a Catamaran sailing adventure with many friends, another blog. We didn’t have a chance to miss home; we were moving too fast for that.

The boat work didn’t start when it should have, and Catmandu (our real home) was still up on stands when we arrived back at the Port Annapolis boatyard. We stayed in a hotel for a week, then moved aboard, entering and exiting via a stepladder to the cockpit.

“It’s like living in a treehouse,” Phil observed. A week later, the boat work was done (the credit cards were severely abused), and we were finally back at home, in the water, ready to enjoy Annapolis. Our old friends gathered on our boat for docktails; we attended the Seven Seas Cruising Association (SSCA) gam2; worked in the SSCA booth at the Annapolis Boat Show; and made new friends. It was almost too “social” for me, but we felt a sense of belonging. It would be hard to leave.

Going Home to NH

New Hampshire is where I’ve spent the most time in my adult life, and where my older son lives with his wife and my grandchild, Lucas. We headed north for a long weekend visit on the occasion of Lucas’s first birthday. How could I resist?

After a brief visit with my sister Janet in Connecticut, we drove through Vermont in mid-October, with the orange, yellow and red leaves of autumn on full display through the Green and White Mountains. I will never tire of this; fall in New England smells like hot apple cider and wood fireplaces. Leaves crunched underfoot as we walked through the orange woods to a clear, cold lake on a sunny Saturday morning.

“I hate to say it,” I said to Phil as we were heading south again, “But this feels like home to me.”

I cried silently the morning we left, hoping Phil didn’t notice as he drove down I-93 back to Maryland. We both knew winter would come eventually and neither one of us wanted to shovel snow or drive in it – or endure the freezing cold. Still, the sadness of leaving stayed with me for miles.

Going Home, Again

We spent just over 60 days at Port Annapolis Marina, enough to realize it was a place that welcomed boaters, specifically sailors, and a place where we could easily be at home. We have friends there and it is just a day’s drive from family. Plus, it has everything a live-aboard cruiser could want: peaceful rivers and coves to explore, a community of like-minded people, and a whole world of boat repair specialists. Perfect! Except, it also has Winter.

It was 7:20 on a chilly October morning in Annapolis when our beloved friends Dan and Jaye helped us cast off our lines. They took pictures as we left the dock and wished us well on our voyage home — that word again.

We were back on Catmandu, with its new coat of bottom paint and freshly repaired rudder and cutless bearing. We flew away from Annapolis with full sails out, speeding down the Chesapeake on a perfect day of sailing – wind on the beam, sunny skies, no engine on. It was, as Phil pointed out, the best and longest day of pure sailing we’ve ever had on our boat. We made it all the way to Solomon’s Island and burned maybe a tablespoon of diesel.

Now, we are heading south and fleeing winter. Our destination, Fort Lauderdale, may or may not be home, but it is a place where we settled years ago, had jobs, joined a sailing club, and still have many friends. It’s the location named on the transom of the boat, our hailing port.

“So, where’s home?” people ask us when we meet at a marina or an anchorage. We usually look at each other because we don’t know the answer. Phil grew up in Minnesota; his family is there. I grew up all over the country; my family is scattered. Instead of explaining our complicated concepts of home, we blurt out whatever we are feeling at the time: Minneapolis, New Hampshire, Fort Lauderdale. Or, the best explanation:

“We live on our boat.”

Home is not always where the anchor drops. Home is where people who love you are sorry when you leave and delighted when you return. By that definition, we are blessed to have many homes: some we visit briefly and return to often, and some we visit rarely and treasure with our whole hearts. For me, home is where Phil is, on Catmandu, the home we bring with us.

Notes

Going Home

Home is where the anchor drops.

— Old mariners’ saying

Going home, going home, I am going home

Quiet-like, some still day I’m just going home.

Morning star lights the way, restless dream all done.

Shadows gone, break of day, real life just begun.

— William Arms Fisher, “Going Home“

“Going Home” was the first song I learned to play on the flute. My father came home early from work every Wednesday to give me flute lessons, starting when I was 10 years old. He had bought a small notebook with blank pages for musical notation and sketched the notes in for songs like “Polly Wolly Doodle,” “Jingle Bells,” — and “Going Home.” (The music was composed by Antonin Dvorak for his New World Symphony, a favorite of my father’s.)

As a child growing up in a nomadic military family, the concept of home was somewhat confusing. From our perspective, home was something temporary. It is the same for Phil and me, now that we live on a moving vessel; it changes from season to season, port to port. Catmandu is our home; we have no other.

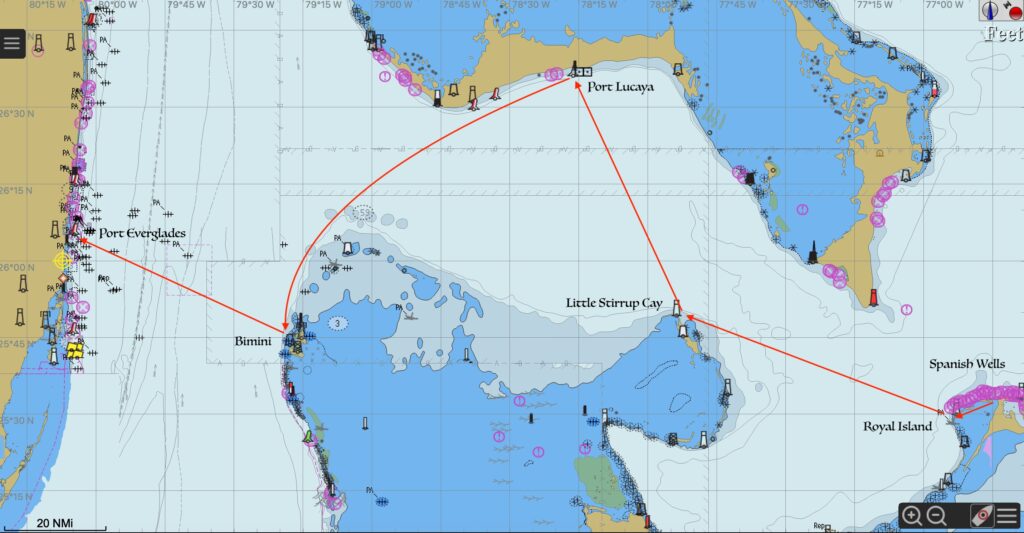

The last time we wrote in this blog, we were in Spanish Wells, Bahamas. The anchorage had emptied out, and it felt like the season was over. Our 90-day permit was up and we were going home.

Going Home, Part One

We allowed ten days to make our way back to the U.S., even though we could do it in four or five. We’ve learned to expect weather delays and mechanical mishaps.

The first leg was a short hop to Royal Island Harbor, four nautical miles to the west. This would set us up for the long crossing to the Berry Islands. We anchored and went swimming, but shortly after climbing the swim ladder, we saw a large creature under the dinghy.

“What was that?” I asked, thinking it was Jaws ready to snack on my bare foot.

“A remora, I think,” Phil said.

“The things that attach to sharks? We were swimming with that?”

“It might have been attached to our dinghy,” he said. I shivered. Ugh. (The ever-clingy remora.)

The anchorage was deserted. We were the only ones there overnight, and left at sunrise the next day. We motored through Egg Island Cut and out into the blue yonder, heading west in a 10-kt south wind.

The long passage to Great Harbour runs through the NE Providence Channel and was pretty rough. We were able to put up full sails on a beam reach and saw speeds over 6.5 knots throughout the morning.

It was a long, 11 1/2-hour day, but the wind and waves calmed to nothing in the afternoon. By the time we reached the anchorage, it was still and the water was glassy. There were cruise ships at Little Stirrup Key (“Coco Cay“), as usual, but only one other sailboat in the anchorage. We enjoyed a bright sunset and a calm night. The next day was a planned rest day.

In the morning, we took the dinghy for an exploratory cruise. We tried to land on a couple of beaches but the surf was much too strong. When the electric motor gave out, Phil had to row us back to the boat.

We went swimming in the clear water after the long dinghy excursion, and again, something scary lurked under the boat. Phil snorkeled to check the hull and the prop, trying to find out why our speed is so slow. I hung onto the swim ladder and the dinghy while he disappeared under Catmandu.

“There is a giant fish under there,” Phil said, as he re-emerged from the water.

“And you didn’t tell me! I went swimming with that?” (I have a healthy fear of sea creatures.)

“Well, after the remora, I thought I’d just ignore this one.” It was a terrible tarpon, probably about four feet long. (Phil says 3 feet.) I’ve heard they like to snack on toes, but I have no proof of that.

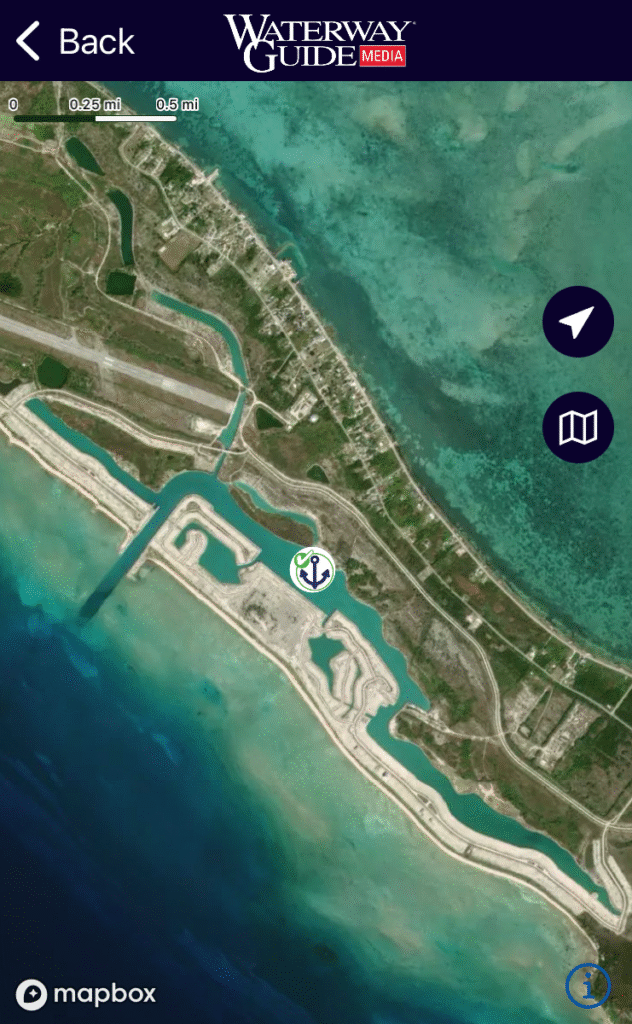

We headed out at sunrise the next day under full sail in a light west wind and made it to Grand Bahama Island, where we once again found a slip at Grand Bahama Yacht Club near Port Lucaya. We had a small problem: the calendar. We needed to depart from Bimini by May 28, and it was Labor Day Weekend. When Phil called ahead for a slip in Bimini, there were none available. Motor yachts from Miami were there for the long weekend, and we were “stuck” at Port Lucaya.

The “Grandma Mama Yacht Club” is our favorite place to stop in the Freeport area, with its sparkling clean pool, Pisces restaurant, and daily shuttle service to a large grocery store (not to mention the nearby liquor store). We had to wait here for the marinas to clear out in Bimini, but we did not mind one bit. We dinghied around the canals, visited the Lucaya Marketplace for tiki bars and restaurants, and watched the weather window for passage to the U.S. As we had only a couple of days left on our permit, we finally secured one night at Blue Water Marina and planned to set out for Bimini.

At 0600, we were ready to go, but Mother Nature had her own plan. We waited out a lightning and thunder squall before pulling in to Bell Channel in stronger winds and higher seas than predicted. We reefed the jib and motor-sailed in 15 to 20-knot winds and choppy 3-foot seas. It was a wild ride! We saw 8.5 knots on the downside of a wave, very fast for our boat.

At around 1 p.m., we passed Great Isaac Lighthouse and the wind calmed a little. Our balky wind instrument finally gave up the ghost, and we sailed on without it. For the last hour, we motored along Radio Beach and then entered Bimini Harbor with very little boat traffic. We tied up at the marina and noted how empty it was. Two rays and a nurse shark passed under the boat in the gin-clear water.

We had one day left on our cruising permit. Winds were high, and without a wind instrument, we wanted to wait for better crossing weather. Would we get in trouble for staying one more night? Luckily, the following morning was bright and clear and we set out for home at 6:45 a.m. The autopilot tried to send us in circles, so we had to hand-steer into the Gulf Stream and compensate for the northward push.

Just to make our homecoming more interesting, the wind and waves entering Port Everglades were wild. We tried to reel in the jib, but in pulling the furling line, I managed to get the sail tangled up and stuck partially furled. It made a deafening flapping noise all the way into the port and Phil had to go forward to work on untangling the mess. We made three bridges and pulled into a slip on an old familiar dock at Loggerhead Marina in Hollywood, Florida, U.S.A. One could say we were “home.”

Four Weeks in Spanish Wells

Twenty years from now you will be more disappointed by the things

that you didn’t do than by the ones you did do.

So throw off the bowlines. Sail away from the safe harbor.

Catch the trade winds in your sails. Explore. Dream. Discover.

— Mark Twain

We pulled up the anchor in Royal Island Harbour and motored the last five miles east to Russell Island, which is considered to be a part of the Settlement of Spanish Wells. Of the three Explorer Chartbooks that cover the 700 islands of the Bahamas, Spanish Wells is covered by the “Far Bahamas” chartbook. We were now in the “Far Bahamas.”

The anchorage near the inlet to Spanish Wells was a little crowded, so we dropped the hook behind the other anchored boats about a quarter mile from shore, maybe a mile from the town.

After a few hours of rest, we lowered the dinghy and took ourselves to a beachside cafe called the Sandbar. We pulled the dinghy onto the beach and anchored it in case of a rising tide. Then we climbed up to the restaurant and took a seat at the bar where we could watch the dinghy being pushed around by the surf.

For the next few weeks, we made our own water, gathered electric power from the sun and listened to the quiet hum of the power station near our anchorage. We did our laundry by hand, ran the generator on cloudy days and explored the quaint town of Spanish Wells. It was the destination we had dreamed of, and we had made it.

Seven Things We Did in Spanish Wells

1. Move to an uninhabited island to hide from wild winds

Two days later, we were looking at wind predictions on Predict Wind and questioning our position. The prevailing wind direction is easterly, and we were nearly unprotected from that direction. The high winds were expected to last for four days, with the worst coming on Saturday. It was the Thursday before Easter; time to move, already.

Phil studied the charts and found a good anchorage with eastern protection just two miles away. The island was called Meeks Patch, and we could see from the cockpit that other ships were headed in that direction. It’s a deserted island except for a colony of pigs and a lone entrepreneur who charges visitors $10 to meet them. He didn’t live there; just brought tourists.

We pulled up the anchor around noon and dropped it next to the deserted island at 1:15. There were a dozen boats here, hiding from the wind, but there was plenty of room. We had a sheltered spot as the winds started to swell and roar through the next few days. We held tight to our Delta anchor and did not drag an inch. During the lulls, we got in the dinghy and explored. We didn’t get back to Spanish Wells until after Easter. Everything was closed on Good Friday, Sunday and Monday. (Easter Monday? Who knew!)

2. Visit the swimming pigs

As the winds subsided, we dinghied to shore after hours when no humans were there to take our money. We saw six or seven large sleepy pigs lying around in the sand, and lots of cute little piglets.

“Look,” Phil said. “It’s an actual pig pile!” Little ones were sleeping all over each other, like puppies. We also saw ducks and chickens.

“There’s a whole barbecue here for meat lovers,” I joked. We are vegetarians, so no temptation for us.

3. Walk on a deserted beach

We explored Meeks Patch on Easter Sunday, taking the dinghy to several beaches where we were utterly alone. The water was shallow and clear, and very warm. We dragged the dinghy onto sand with not a single footprint and felt like explorers. It’s not that unusual to find deserted beaches here, and we enjoyed leaving a trail of prints in virgin sand.

4. Ride the tide into a perfect beach

After the winds calmed down, we headed back to our Russell Island anchorage, picking the same spot we had left just four days earlier. It was about a mile to the main channel into town, and a mile to the Sandbar, where we often went for happy hour. It was time to explore Spanish Wells, just a short dinghy ride to the east.

One of our first discoveries was an incredibly beautiful beach where the tide changes rushed in and out, turning dry sand into shallow pools of clear water. The incoming tide is so strong, people make human rafts and lift their feet up, letting the current wash them into the channel.

We visited this beach twice, and Phil snorkeled through the incoming tidal current. I packed a picnic and we made a day of it. This beach is adjacent to a park and features a beach swing, which is pretty hard to get into at low tide. I tried.

5. Visit every single restaurant

As far as we could tell, there are just four (or maybe five) restaurants in Spanish Wells, and we hit them all. The fifth is the Eagle’s Landing, which we thought was a private club, so we didn’t try it. We visited the Sandbar by dinghy, Wrecker’s at the Spanish Wells Yacht Haven, the Shipyard at the eastern end of the town, and Budda’s Snack Shack in the middle of the island. Near Budda’s is Papa Scoops, a local ice cream shop serving homemade flavors like Cheesecake and Oreo Cookie, but it’s only open two hours in the evening and only makes two flavors a day.

All of the restaurants are accessible by dinghy, but the Shipyard dock is in very shallow water so we could only get the dinghy in at high tide. The only dolphins we saw in the Bahamas in the three months we were there were in the main harbor on our way to Wrecker’s. They were small and brownish colored and swam right in front of our dinghy.

6. Rent a golf cart and explore

Spanish Wells is walkable if you don’t mind a mile or two. From the harbor, where we entered the town on our dinghy, you can reach a grocery store, snack shop, two marine stores, two restaurants and a liquor store all within a mile. On the other, farther side of the island are the larger grocery store, the post office, gift shops and a hardware store. We wanted to explore the whole place so we rented a golf cart. There are more golf carts in Spanish Wells than cars. Note: they drive on the left, so we had to be very careful, especially when turning right.

The plan was to drive the full perimeter road and discover what we might have missed in our dinghy runs into town. Along the way, we found a gift shop with picture post cards and sent some to family — once we found the tiny post office. The one large grocery store is a pretty long walk from the dinghy docks, so we visited by golf cart.

We crossed the cute bridge by our favorite beach and discovered another beautiful beach around the corner. We followed some winding roads up into the bluff above our anchorage and took a picture of our boat at anchor (the picture is the first one in this blog, above). There are some incredible homes with amazing ocean views up there on the hillside. After getting a little bit lost, we found our way back to town and stopped for lunch at Budda’s.

7. Meet the people

The first people to arrive from Europe were a group of Puritans escaping England to practice their religion freely. After a stop in Bermuda, they sailed on to Eleuthera and wrecked their ship on the Devil’s Backbone, surviving by sheltering in a cave. The year was 1647. The Eleutheran adventurers as they are called, ate fish and found fresh water in the wells dug by Spanish treasure hunters, giving the town its name. The Spaniards had used the island as a last water stop before crossing the Atlantic.

Because it was so remote from other inhabitants of the Bahamas, the people who settled here developed their own native accent, which you can still hear when the locals talk. It’s hard to describe, but it sounds a bit like an Irish lilt. Today, fewer than 2,000 reside here full time, and it is the only majority white district in the Bahamas.

The people here say hello when you pass on the street. The bartenders and servers are friendly and proud of their community. The cashier at Pinder’s Market spoke with the native accent and told us she was born and raised on the island. We recognized the accent in the speech of servers at Budda’s and the bartender at the Shipyard. A stranger on the beach told us about her life on the island, all in the British/Irish lilt of Spanish Wells. It’s a small, close-knit group of families who are proud to belong here.

It’s Time to Go Home

Phil threatens to turn himself in at the Bahamas Immigration office and slap his U.S. passport on the desk, screaming “I defect!”1 but I’m not sure that’s the way to extend our stay. We had 90 days to be in the Bahamas, and our time is nearly up. Besides the permissions expiring, there is also the problem of getting my medications for Type 1 diabetes and cancer, and a round of medical scans scheduled for the first weeks of June back in Florida. We could have had a one year permit for twice the money, but I would still have to go back for medical reasons.

We are slow cruisers, and maybe we didn’t see every tourist spot in the surrounding islands. But we got to know this place, and its people. We lived off the grid for over a month, relaxing on the boat most afternoons, or riding in for happy hour. It was a month; but we could have stayed longer. Maybe the next time we’re here, Phil really will defect and we’ll settle down in one of those little cottages with the wide open porches. If we ever go missing, look for us here first.

- Very arcane reference to Robin Williams in “Moscow on the Hudson.” https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Moscow_on_the_Hudson ↩︎

Uneventful

Sailing is 90% boredom punctuated by 10% sheer terror.

–Author John Casey

Even though our sail repair parts were sitting in the same port just a few miles away from us, it took eleven days to convince FedEx and the Bahamian customs officials to hand them over. Phil repaired the mainsail in a couple of hours, and we left Port Lucaya early the next morning bound for Great Harbour in the northwest Berry Islands.

When traveling for pleasure, one doesn’t usually wish for “boredom” or for a trip that is “uneventful.” But for us, it is a victory when we get where we’re going without breaking anything. We didn’t.

Port Lucaya to Great Harbour

We motored out of Bell Channel and put out the jib before raising the mainsail, putting a happy grin on Phil’s face. But as the mainsail reached the top of the mast, a loud bang rang out and I ducked, thinking something heavy would fall on my head. We looked at each other.

“What now?” I said. Phil inspected the sail rigging at the mast and came back to the cockpit.

“I broke the boom vang,” he said.

A month ago, I would have said, “The what?” But we had seen one of our Youtube sailors break his boom vang just a few weeks earlier, so I knew. Phil tied it up for stability and I asked what it meant for our setup.

“Not a thing,” he said. “I never use it.” We will ask our rigger to repair it when we get back to Florida, but until then, it’s just another broken thing on the boat. We keep a list of “broken things.” During the afternoon, we noticed that the wind instrument was not working and that one of the three filaments in our Dutchman Flaking System had snapped.

The rest of the 60-nm trek to Great Harbour was uneventful, motoring with full sails to keep up a speed of 5.5 to 6.5 knots so we could arrive in daylight. The chart plotter noted that it was ten hours between waypoints. We had calm seas with a current that ran against us in the morning and with us later on as we approached the Great Harbour anchorage.

The islands to the west of the anchorage are used as playgrounds for cruise ships, and we saw three of them on our way in. Royal Caribbean calls Little Stirrup Cay “CocoCay” and leases the island for its passengers to enjoy their “Perfect Day,” with a water park, skidoo rentals, snorkeling areas, beaches, aerial ziplines, and a full-size helium balloon that takes passengers 450 feet into the sky on a tether. The water park has towering water slides, the Caribbean’s largest wave pool and a lazy river, all watched over by more than 100 lifeguards.

There were two other boats anchored off of Goat Cay when we arrived. We looked for a large sandy area to drop the anchor, and when Phil found the perfect spot, I took the helm. He went forward and lowered the anchor. Then when he asked me to reverse, I shifted and somehow got it stuck in reverse (it was revving too high to shift) so I could not get it into neutral.

Going in reverse, I ended up pulling the anchor out of its perfect spot and dragging it along as I struggled with the transmission in a panic. Phil yelled for me to slow the engine as we were in danger of plowing into the boat behind us, and with that I was able to shift to neutral. Of course, we had to start all over. That was my 10% of terror.

Safely anchored, I apologized to Phil and we both decided I needed more time at the helm so it would become second nature, like driving a car. A cocktail or two went by and we watched the sun go down over CocoCay. We turned to the east, anticipating the appearance of the full Pink Moon of April. It rose above the trees just a few minutes past sunset, and it wasn’t actually pink. Native Americans called it the Pink Moon because of the pink flowers that bloomed in early Spring.

That wasn’t the end of the fun in the sky. There was a SpaceX Starlink launch from Cape Canaveral later that night, so we went out to watch. We could see the glow of the second stage as it crossed overhead, a plume of light gray and white mist surrounding the speeding spacecraft. The bright flare of the re-entry burn lit up the sky as the first stage made its turn to descend to a drone ship east of the Bahamas. It was a show worth watching.

The next day, Phil repaired the filament on the mainsail’s Dutchman Flaking system and re-folded the sail. It was a day of rest, brilliant and calm. We watched an impossibly large turtle lift its head out of the water, take a breath and descend. We both saw it. Usually only the first person sees the turtle. By the time the second person looks for it, it’s gone.

Great Harbour to Royal Island

The wind was blowing out of the northeast at around nine knots when we left the harbor early the next morning. I took the helm as Phil pulled the anchor at 7:30, and needing the practice, I drove for a while as Phil put up full sails. It was a perfect partly cloudy day with bright sun and temperatures in the mid-seventies. We motor-sailed through the morning. This was a long passage and we wanted to arrive at Royal Island in the daylight. It’s dangerous and scary to anchor in unfamiliar waters in the dark, so we try to time our trips in daylight hours.

As the wind was building, we turned off the engine to see if we could sail fast enough to make it to our destination by 6. We couldn’t; the speed slowed to 4.5 knots under sail alone, which is a great pace if you don’t have a deadline. We enjoyed the few minutes of quiet and reluctantly restarted the engine.

By mid-afternoon, as we crossed the open waters south of Great Abaco Island, the seas began to build and the wind picked up. Phil expected this to happen, as we were in the middle of the Northeast Providence Channel, a passageway known for heavier wind and currents. To our south, New Providence Island, home of Nassau, was more than 60 nautical miles away.

We started to speed up and heel over, with winds picking up from 15 to 19 knots with gusts over 20. The sails were full and the waves were exceeding three feet, with some building to four feet. Catmandu leaned into it, heeling over 15 degrees with an occasional 20. We were overpowered and started to think about reducing our sails. The speed was fun, but a little scary as we slid down the higher waves and pounded into the white-capped ridges. The clouds rolled in and we started to feel chilled.

******

Heeling: a basic process affecting all sailboats

which begins with the boat leaning over…

and ends as the sailboat finally exhibits its natural tendency

to come to a state of rest on the sea bottom.

–from Sail-ing, by Henry Beard and Roy McKie

******

Phil decided it was time to furl the jib completely and spill some air off the main, which made it much more comfortable. We rounded Egg Island and Phil hand-steered through Egg Island Cut, a narrow gap between the small cays. Egg Island was named for the many birds nesting there, where early sailors could go ashore and gather eggs for food. But someone had the bright idea of pasturing goats there, and that was the end of the eggs.

Early in the day, Phil had texted two boats anchored in Royal Island Harbour (found on the phone app, “No Foreign Land,”) asking if there would be room for us. Both captains assured us there was plenty of room. We dropped the mainsail and pulled into the small harbor at 5:30pm, finding just a few other boats. I was anxious to redeem myself as a good first mate as Phil went forward to drop the anchor and I took the wheel. The anchoring was uneventful — the anchor set right away and held.

After the wild ride in four-foot choppy seas and high wind, we were ready for a rest. A small green turtle wandered by, this one in no hurry to dive. We sat in the cockpit with gin and tonics and watched the sun go down. Our new surroundings in Royal Island Harbour were quiet, calm, and lovely, protected on all sides. We don’t consider this boredom; we think sailing is 90% peaceful. We will sit for a time while the sky fades into pink and periwinkle, and wait for the ibises to gather in the trees.

“Tell me, what is it you plan to do

With your one wild and precious life?”

How Do We ….

I shared this insight with some other boat owners, and they all agreed that,

definitely, putting your boat into the water is asking for trouble.

— Dave Barry

We have been living on Catmandu while anchored in the Bahamas for almost a month now, spending much of our time in Spanish Wells. Life on the anchor is different than life at a slip, i.e. “dock,” at a marina. At a marina slip, we have electricity and water hookups that we can just attach to the back of the boat. Laundromats and grocery stores are a short walk away. On anchor, we have to do a lot of things on our own.

Do Laundry

Did you know that the town of Spanish Wells, Bahamas, has NO laundromats? We knew that before we arrived. Some larger sailboats with more electric capacity have clothes washers built in. Our boat, Catmandu, simply does not have space for it. We could probably run a washer with our Honda 2200 generator, but we choose to do our laundry with arm power. This is our washing machine, a hand-cranked manual device called Wonder Wash. We saw it on one of our favorite Youtube sailing channels. It holds about 6 pounds of laundry, or about half of a normal load. We put in the clothes, four tablespoons of detergent, and 8 quarts of warm or cold water, and start cranking. (As Phil says, “Every day is arm day on a boat.”)

After turning for a few minutes, we rinse, drain, and repeat. Then the wet wash goes on the lifelines and dries in the sun and breeze. We have just enough clothespins to hang one load. For large towels and bedding, we have to find a laundromat on land, and most marinas have coin-operated machines for cruisers. Hard core cruisers would otherwise use a plunger and five-gallon bucket. No thank you!

Make Electricity

We have three ways to generate electricity for living on our boat. Some of the electricity has to be direct current, and some has to be alternating current. For strictly AC current needs like charging our laptop computers or the electric outboard motor batteries, we have a small 200 watt inverter that plugs into the cigarette lighter outlet at the navigation station.

1. Solar Panels

Catmandu has two 200 watt rigid solar panels mounted on the dinghy davits at the back of the boat. The solar panels generate up to 400 watts of DC electricity that is controlled by a multi-stage charge controller and feeds electricity directly into our house battery bank. Our charge controller is Bluetooth enabled so we can monitor the battery state of charge and other statistics using an app on our smartphones. It is very geeky, so Phil likes it a lot. We can angle the panels somewhat to chase the sun, as seen below.

2. Generator

Our Honda EU 2200i inverter / generator runs on gasoline and produces up to 2200 watts of AC power. We need to use the generator to make fresh water, but we also use it to charge our batteries on cloudy days and charge up our laptop computers. To charge the batteries, we attach a 30 amp shore power cord to the generator and the back of the boat and turn on our built-in battery charger. When used this way, the household AC outlets on the boat are also live and we can plug in other things. The generator can also power our air conditioner when we are at anchor. Our Honda is also Bluetooth enabled and comes with a smart phone app that shows us how much power it is presently generating and alerts us when it is time to perform periodic maintenance. It is oh so geeky.

3. Alternator

This year, we upgraded the alternator attached to our diesel engine to a 100 amp, high-output Balmar alternator with a multi-stage external regulator. Like any alternator, it makes DC electricity and charges the boat’s batteries. Is it also Bluetooth enabled? No! But we could add a $230 electrical monitor to add Bluetooth, and we have not done so. That would be too geeky.

Make Drinking Water

Catmandu’s fresh water tanks hold a total of about 90 gallons, but we can run through that in about four days of regular use when not trying to conserve water. To make drinking water. we run our portable Rainman water maker. The Rainman “desalinator” works off the principle of reverse osmosis (“RO”) to pump seawater through filter cartridges having pores that are so small that salt molecules and contaminants cannot pass through them. A first component has a pre-filter cartridge and a high pressure pump. A second component is in a case that holds two large reverse osmosis filters, a pressure gauge, and a flow gauge. Eight hundred PSI is required to force the seawater through the RO filters. Our model runs off AC power and makes about 40 gallons per hour. When at anchor, we just plug the water maker into our Honda generator and run it twice a week.

Every day is arm day on the boat!

— Phil Decker

Some marinas in the Bahamas charge up to 80 cents per gallon for fresh water! Filling Catmandu’s water tanks would cost $72, and we would have to do that twice per week. Instead, when we are at a slip in one of those marinas, we run the water maker off of shore power instead of the Honda generator. It takes a cup or two of gasoline to run the generator for a couple of hours. When not in use, the water maker components are stored in the aft lockers in the cockpit.

Make Hot Water

There are two ways we can make hot water for taking showers onboard when at anchor. Usually, we run the Honda generator. We control the electric water heater with a switch on the instrument panel. It takes about a half hour to completely heat our six gallon hot water tank. The second way is to run the diesel engine. The diesel has a clever loop in the cooling circuit that goes under the floor to the hot water tank under the galley sink. There is a heat exchanger inside our water heater tank so the engine coolant does not mix with the fresh water. It is very nice to be able to take a hot shower after a long day of sailing.

Avoid Seasickness

Kay has an issue with motion sickness and gets nauseated and dizzy in rough sea conditions. It runs in the family, and some members of her bio-family have much worse cases. Please do not tell people who suffer from this condition that it is “all in your head,” or “just look at the horizon, it will go away.” It is not psychosomatic and requires treatment if one wants to live on a sailboat.

Kay uses a relief band ($129) for mild sea conditions, and a combination of Dramamine (meclizine) and relief band for more active seas. One valuable tip: Take the Dramamine the night before travel. You’ll sleep well, and the medicine is effective for 24 hours. Otherwise, the medicine will force a nap within 3 hours or so (even the non-drowsy formula).

The relief band is an electronic device worn on the wrist that provides an electronic pulse. Or, as the website explains: “Relief Band utilizes the principles of neuromodulation to relieve nausea. The device emits gentle electrical pulses that stimulate the median nerve, which in turn sends signals to the brain. These signals help to restore normal gastric rhythm and reduce the sensation of nausea.”

The website indicates that it has an 85% success rate, so it doesn’t work for everyone. To Kay, it is a lifesaver.

Bake Bread and Pizza

Phil got the knack for making bread from working at a pizza joint in college. Now he makes French bread and pizza crust from scratch, and bakes them in our propane oven onboard.

Get on the Internet

There are two internet / telephone providers in the Bahamas: BTC and Aliv. We tried both, and Aliv is much better. We bought a block of 125 GB of data only, and Aliv provided a new mobile hotspot for only $9 more. The Verizon mobile hotspot we use in the US cost over $200, so the Aliv deal was great. We make phone calls, send and receive e-mail, browse the internet, and participate in Zoom calls easily when we are in cell tower range of any Bahamas island. The mobile hotspot works off a USB cable and uses very little electricity. We keep it on 24/7.

When offshore, we have the Iridium Go! satellite communication system that we can use for e-mail, text messages, receiving weather data, and voice calls. It is battery operated and charges with a USB cable. It uses very little electricity. However, Iridium Go! is very slow and cannot be used to browse the internet. It is primarily for offshore and emergency use.

Q: Why not just use Starlink? It is very fast and has high bandwidth even when offshore. A: It is more expensive, and uses a great deal more power. For example, the Starlink Mini uses 25 – 40 watts of AC power continuously. More popular Starlink units run at 100 watts. That is simply too much power to keep the unit on all the time, and we have no need to be able to stream Netflix from the middle of the ocean.

What will we do when we are too old for all this?

Phil has a dream. What aging sailors need is a place to live out their lives on their sailboats, motor yachts or trawlers. His dream is to develop an assisted living marina.

Presenting The Grandma Yacht Club

The dock pedestals will have pull cords, in case you’ve fallen and can’t get up.

The slips will have chair assists to get you on or off your boat, like you would see at a public swimming pool.

The docks will have edges to keep the wheelchairs from going into the water.

There will be a tiki bar for happy hour, and of course, weekly Bingo.

Remember the Main!

The definition of “cruising” is fixing your boat in exotic locations.

— Author unknown

After enjoying Bimini for almost two weeks, I picked a windless morning in mid-March at Brown’s Marina to raise our mainsail at the slip. I wanted to test the new Tides Marine plastic, low-friction mainsail track that our rigger had installed just two days before we left Florida. We did not even need the mainsail when we motored across the Gulf Stream to the Bahamas because there was no wind. However, we would likely need the mainsail for sailing to West End on Grand Bahama Island the next day, and I needed to make sure everything was working properly at the dock before heading out to sea — where things are harder to fix.

The sail Would. Not. Go. Up.

The mainsail is heavy, so I used the heavy-duty electric winch for persuasion. It only went up part way and then became hopelessly stuck. Releasing the winch, I tried to lower the main. Now, it would not go down! After hanging my full weight on it and bouncing, it finally came all the way down. What was the problem? The mainsail went up and down fine with the old plastic sail track, but would not go up with the new one.

Let’s back up to January and February to explain how we got into this predicament. Our boat mortgage requires us to always have boat insurance. Boat insurance covers sailing in the US, but coverage in the Bahamas requires an insurance endorsement. To get the insurance endorsement, our insurance provider required us to get a hull survey (“inspection”) and a “rigging aloft” survey. The term “rigging aloft” means the mast, boom, spreaders, shrouds, stays, and running rigging. The hull survey went fine. Our regular rigger was then able to perform the rigging survey. Everything was mostly fine, except that he said our old, plastic sail track was cracking and should be replaced. The danger of not replacing sail track is that the mainsail could get stuck in the up position and we would not be able to lower it when we needed to. The choice was clear, we had to replace it. However, the rigger was unable to finish the installation until two days before we sailed. There was no urgency to test it after installation, since it is so simple that nothing could possibly go wrong.

Back in Bimini, we were ready to jump to West End during a short weather window in the middle of March. I scoured the Tides Marine website to figure out the problem. The sail track is a long, low-friction plastic track that is attached to the mast on one side and has a long slot on the other side. Stainless steel sliders are attached to spaced locations on the mainsail and have a flat part that slides up and down inside the slot when the mainsail is raised and lowered, and another part that attaches to the sail. Simple!

The Tides Marine website, however, disclosed a slider manufacturing defect that lasted for several years, and that has long since been corrected. The result was that the old sliders with the manufacturing defect did not fit the new sail tracks. The sliders would get stuck in the track, and that was our problem. We had to get a replacement set of sliders and install them ourselves in the Bahamas.

We motor sailed 64 miles from Bimini north to West End using our engine and jib sail. It is about an 11 hour trip. We were quickly outside of cell tower range, so I deployed our Iridium Go!® satellite communication system. I sent text messages and e-mails to both our rigger and Tides Marine to get an order placed as soon as possible. I did not want to lose even a single day. We were going to be in Freeport / Port Lucaya in a week or two, and that is one of the easiest places to get parts shipped in when in the Bahamas.

Tides Marine was wonderful to deal with. They acknowledged the manufacturing defect, and agreed to provide and ship the replacement set of sliders to us for free. The retail price of the replacement sliders was about $1000, and shipping from the US to the Bahamas would have cost hundreds.

Getting boat parts shipped to another country is more complicated than shipping to destinations in the US. The quintessential way that you read about in the cruising guides and online is as follows. You get your parts to the US base of a tiny Caribbean airline like Makers Air. Their base is at a small airport outside of Fort Lauderdale. The airline puts your package on a puddle jumper airplane and they land at an airstrip somewhere close to you in the Caribbean. You hire a “customs broker” of your choice to navigate the impossible-to-understand paperwork. Think like you’re hiring a bail bondsman, picking him out of a list of names in the phone book. In my mind, a customs broker is a mustachioed man in a Panama hat and loud tropical shirt who may or may not have to pass the customs man a $50 to get your goods out of the pokey. Instead, I chose FedEx.

Why not ship FedEx? There are 700 islands in the Bahamas, but there are only two FedEx offices in the whole country. Fortunately, we were going very close to the one in Freeport, which is just five miles from Port Lucaya, our marina destination. I told Tides Marine to put my name on the shipping label and “hold for pickup.” As a cruiser, I have done this for other shipments in the US, and it seemed like the most straightforward way to get my shipment.

I checked the status of my shipment online daily using the tracking number provided by Tides Marine, and for 11 days it said “waiting for customs clearance.” I phoned FedEx customer service almost every day to see when the shipment would be released and if there was anything I needed to do. Each time, the agent told me the release would be very soon, and there is absolutely nothing I needed to do to receive my shipment. I asked whether I should go to the FedEx store in Freeport and talk with a representative. Absolutely not!

So, the next day I took a taxi the five miles to FedEx store and back so I could talk with a representative in person. The taxi cost me $80 round trip. That was very steep, but I understand they have flat rates on Grand Bahama Island. I had considered walking. However, my taxi was a spotless, unmarked black Range Rover driven by “Mr. Forbes” in a starched, white button-down shirt, who waited for me outside while I did my business with FedEx. I paid the fare, realizing it was just the cost of doing business to get my parts so we could repair our mainsail and sail on to our next destination.

At the FedEx store, the clerk was very helpful and very friendly. The steps for receiving an international package were clearly printed on a poster hung on the wall, and I had never heard of any of these steps in any cruising guide. I will share them with you so that you will not have to suffer the delays that we did:

- Create a user ID and password on the Click2Clear website and register as an “importer.” There is no charge for this, and needs to be done only once. Cruisers in the Bahamas are required to use Click2Clear to apply for a cruising permit, but there is otherwise no need to create a user ID and password. FedEx registered me as an importer while I waited at no charge.

- Fill out Bahamas Customs Form C44, which allows FedEx to act as my customs broker. They also had to scan my passport.

- Present an original invoice and/or receipt for the goods showing the description. FedEx accepted the PDF invoice that Tides Marine had sent me by email.

- Email all documents to FPOIMPORT@FEDEX.COM with the tracking number in the subject line.

After all that, the FedEx rep said Bahamas Customs could release my parts as soon as tomorrow. I received an email the very next day that my package had been released!

Instead of spending another $80 on a taxi, I found that I could take a “public bus” for about $2 each way. There is no bus schedule, there is no route map, and the bus stops are unmarked. But they show up every 30 – 60 minutes or so and somehow get you close to your destination. The “buses” are beat-up Mitsubishi minivans and the driver is usually playing Bahamian “rake and scrape” music on the radio enthusiastically. The buses themselves are a trip, the drivers and passengers are friendly, and I always got off the bus smiling. I took a public bus to FedEx and back and saved myself about $76 in taxi fare.

I had to pay import duty and pay for FedEx as my customs broker. All in, the fees came to about $50.

The next day, with 18 pieces of highly machined stainless steel of three different sizes in hand, I undertook the chore of replacing each of the old, bad sliders with a new one. This involved partially raising the mainsail at the marina slip so that I could remove an old slider one at a time and install a new slider — without having the mainsail catch the wind and cause damage. The chore took most of a day. I tested my work by raising the main all the way up to the top and letting it drop when I released the main halyard. Catmandu finally passed the test. Now, all we had to do is wait for the wind to change.

“Remember the Main”

The actual phrase is “Remember the Maine,” a slogan of the Spanish-American War following the explosion of the US battleship Maine in Havana Harbor in 1898.

The Sailboat that Couldn’t Sail

Dreaming is happiness. Waiting is life.

— Victor Hugo

If we learn to enjoy waiting, we don’t have to wait to enjoy.

— Kazuaki Tanahashi

Our easterly route from Ginn Sur Mer followed the southern coast of Grand Bahama Island, which looked nearly deserted until we got closer to Freeport. The marine traffic picked up as we neared the harbor entrance, with a few huge cargo ships and tankers. Something was burning in Freeport, sending up clouds of heavy smoke. There were terminals out in the water for the tankers to offload oil and gas. It all seemed ugly and industrial to me after the deserted natural beauty of Ginn Sur Mer.

After hearing other boaters calling for the “Grandma Mama Yacht Club,” we finally got our slip assignment and pulled easily into the C dock at Grand Bahama Yacht Club. This would end up being our favorite marina on this trip, even though we were stuck here waiting for boat parts (we still could not raise our mainsail) and a weather window. It’s not bad being stuck close to town with a pool, a pool bar and a restaurant, in a slip near the bathrooms and laundry.

We were docked next to a large catamaran called Isle of Misfits, with artwork depicting the Misfit Toys from the Rudolph the Red-Nosed Reindeer cartoon-movie. After tidying the lines and fenders, we headed to the pool bar for a celebratory beer, unaware that it didn’t open until 4. As we sat waiting for a bartender to arrive, two men sat down next to us at the bar.

“Are you our new neighbors?” one asked. “We are the Misfits.” We introduced ourselves and gave them a boat card. We chatted about our boat names, mentioning that we were waiting for sail parts that might arrive in Freeport any day now. Just before they left, one said to me, “I just realized that you are misfits, too. Remember the boat that couldn’t float? You are the sailboat that couldn’t sail.”

(For a great laugh when you need one, please read Ben Bowman’s ranking of the Misfit Toys.)

Life at Grandma Yacht Club

We settled into marina life, filling our days with cleaning chores, laundry, and a couple of trips to the large grocery store (Solomons) in a courtesy van. The marina offers rides every weekday at noon. I also had to have blood drawn for my oncologist in Fort Lauderdale, and Phil found an in-network lab we could walk to. (To be honest, I really couldn’t. I was out of breath and in pain by the time we finished the mile and a half in the hot sun. We took a taxi back.) Meanwhile, we waited for our package. Phil called, emailed, and visited FedEx and Customs. The first visit to the FedEx office cost $80 for the taxi. He found the city bus after that ($1.50).

On laundry day, we went to the office for quarters, and Phil wanted to take a picture of the marina sign. He brought along a burgee (flag) he’d saved from his first visit here on his neighbor’s sailboat 19 years ago. As we were posing, we asked a dock hand to take our picture – and he stared hard at the flag we were holding.

“Where did you get that?” he asked.

“Right here, 19 years ago,” said Phil.

“I think I gave that to you,” he said with a grin. “I’m Fabian. I’ve been here 23 years. I recognize that old flag.”

We were VIPs after that, and people at the pool told us they heard the story from Fabian. We flew that flag, our VIP flag, for the rest of our visit.

We loved the swimming pool and visited often. It was cold, but clean with a waterfall and bridge at one end and lanes for laps. We struck up conversations with other boaters there, and learned a little about Port Lucaya, the ferry service, and a place to dock the dinghy near the bars and restaurants at the market square. We also encountered a woman walking a large black pig like a dog. “Oh, that’s Chris,” Phil was told. “Short for Chris P. Bacon.”

Back in the Dinghy Again

Of course, our favorite pastime while we waited for sail parts was dinghy rides. We were advised by various cruising guides not to anchor within sight of the marina. We went into the canals to find alternate anchoring spots, but every one of the possible sites had a no anchoring sign.

Along the way, we found derelict boats, derelict houses, wrecked docks, and a few construction sites. One large marina adjacent to Port Lucaya Marketplace is completely wrecked, even worse than it was when we visited by land several years ago. No one seems to be interested in repairing it.

On one excursion, we came across this boat, and Phil said, “Now there’s a boat I could afford!”

Phil called it a tramp steamer. For some reason, it reminded me of a scene in a movie that I couldn’t quite remember.

“Wouldn’t it be fun if there were monkeys,” I said.

We both laughed because I realized that must have sounded like a random thought to Phil, not knowing what I was trying to remember: a movie with monkeys taking over a similar boat. (If you know what I was thinking of, please identify the movie in the comments.)

We took the dinghy to the Port Lucaya Marketplace several times, parking it near the ferry landing by Sabor’s Restaurant. We walked around the shops, restaurants and bars, buying very little. At Happy Hour, we sometimes found ourselves at Rum Runner, where the music was loud and often featured American country.

We talked with other patrons at the bar: a pair of flight attendants from Texas; a “Conchy Joe” who explained that his nickname was what they called White Bahamians; and other travelers who sipped the tall, icy concoctions made by the busy Bahamian bartenders.

Three weeks slipped away, and we were still waiting for the sliders that would fix our mainsail. Phil will tell that part of the tale, but as he did everything he could to unite us with our package, we enjoyed the amenities and camaraderie of Grandma Mama Yacht Club. Until the day before we left, Catmandu continued to be the embodiment of a misfit toy: the sailboat that couldn’t sail.

The Lamb and the Lion at Ginn Sur Mer

If humans just disappeared from the world, and you could come back to Earth … one year later,

the first thing you’d notice wouldn’t be with your eyes.

It would be with your ears.

The world would be quiet.

—Carlton Basmajian, Ph.D., Iowa State University

The Unrealized Resort

The Ginn Sur Mer development on the southwestern coast of Grand Bahama Island is not a ghost town. Despite its roads, stop signs, electrical lines and dredged waterways, it was never a town at all. No one ever lived here and only one house was ever built. The developers envisioned golf courses, luxury homes, hotels, restaurants and room for mega yachts.

After the Ginn company defaulted on a $650 million loan, Credit-Suisse foreclosed on the property in 2010. Although the government was eager to find new investors, work stopped on the luxury property. The original developers left wide canals with stone sea walls and a 14-foot deep anchorage with room for 9 or 10 boats.

When we arrived there were three other boats in the anchorage but by the time evening came around, there were nine boats in the basin and one catamaran in the canal to the east. A stiff wind was predicted for the following night so anyone in the area looking for a safe refuge didn’t have many choices. It is really the only protected anchorage in this end of Grand Bahama Island, which is a very long island.

We were anxious to explore all the little canals, and after a brief friendly visit from one of our Canadian neighbors, we climbed into our dinghy to take a look around. “Deserted” doesn’t begin to describe the eeriness of this area. The sandy roads have stop signs at intersections, and a completed bridge crosses over the canal. The vegetation consists of low shrubs and trees that crowd in on the few cleared lots.

We wandered around in the canals using our quiet Electric Paddle® electric motor, coming to a couple of small lakes where the canals ended (see the chart above). Because the waterways are lined with stone seawalls, there was no way to beach the dinghy and explore on land. The wildlife was silent; we didn’t even hear birds singing. We saw one turtle on the way into the basin, but no fish, turtles, dolphins or land animals after that.

We wanted to see the one house that was built, and found it on the canal closest to the beach. It stands on the beachfront, about three stories high, with a large garage and a finished roof. It looks ready for occupation, but no one lives there. Of course there are no nearby services except for the few amenities offered by the settlement of West End, four miles away over half-finished roadways. Our Canadian neighbors told us they had entered the house and looked around, but we were not about to trespass, no matter who owns the property.

The Big Blow

Phil keeps a close eye on wind predictions, so we knew a big wind was about to blow. The harbor was crowded because of the wind forecast, and the crowded anchorage made high wind much more dangerous. For inexperienced boaters who don’t exactly know how much chain to put out with the anchor, there is a danger of dragging and hitting other boats. But even for seasoned sailors, high winds can dislodge a well-placed anchor, and most cruisers have dragged their anchors at one time or another.

We were nervous about the 25-knot wind predictions. It doesn’t sound like a lot until it is howling above you and rattling your boat’s rigging. This wind began to whirr at sunset, and by ten o’clock, we were seeing 20-knots on the wind instrument. The wind howled above us. The shallow anchorage was whipped up to a froth and the waves rocked the boat. The sustained winds reached 25 knots with 27-knot gusts.

I tried to sleep, but Phil stayed outside and monitored the anchor watch. It was pitch dark, except for ten anchor lights and the cockpit lights of a few other boats with skippers staying at their helms, also on anchor watch. The concrete seawall on one side and coral ledge on the other side of the narrow channel were invisible except on the chart plotter.

At 11 pm, Phil saw on the chart plotter that our anchor had been briefly dislodged and had dragged about 25 feet before catching again. For the anxiety that caused, he stayed at the helm all night, finally coming to bed at 4:30 am. I offered to finish out the night, but he said the wind would die down soon. It was 7:30 am before we heard the wind settle down, just as the sun rose.

We stayed at Ginn Sur Mer for one more night and on Saturday morning we tried to raise the anchor. Phil pulled up as much chain as he could with the anchor windlass, but it wouldn’t budge from the bottom. He directed me to motor forward slowly, first to the right and then left, as he moved the chain in different directions. The anchor was wedged down tightly, and due to the high winds, it had been pulled with a lot of force, possibly under rocks.

After 20 minutes of maneuvering back and forth, Phil told me to motor forward and finally got the anchor off the bottom. If we hadn’t been able to free it, the alternatives were limited: let the anchor go with 150 feet of attached chain, or dive into murky water to attach another line to help pull it up. Luckily, we didn’t have to make that decision.

We love the peace of a deserted anchorage, being off the grid with no motors running. It is so often ruined by inconsiderate people in their loud boats and even louder music. And nature itself sometimes gets loud: howling winds, waves crashing, laughing gulls, ospreys, and (sometimes) ocelots. But after the boats leave and the winds die down, there’s just the musical lapping of ripples against the hull. Phil calls it happy boat sounds. My word for it is quiet.