“In a field

I am the absence

of field.

This is

always the case.

Wherever I am

I am what is missing.When I walk

I part the air

and always

the air moves in

to fill the spaces

where my body’s been.We all have reasons

for moving.

I move

to keep things whole.”– Mark Strand, Keeping Things Whole

Our plan, to the extent that we had one, was to explore the quirky environs of Key West and take a week or so in the Dry Tortugas for some snorkeling and walks around the historic fort. Then, when the weather and wind were right, we would turn eastward and jump over to the Bahamas for a season. True to the cliché, “cruisers’ plans are written in the sand at low tide,” ours changed – for very good reason.

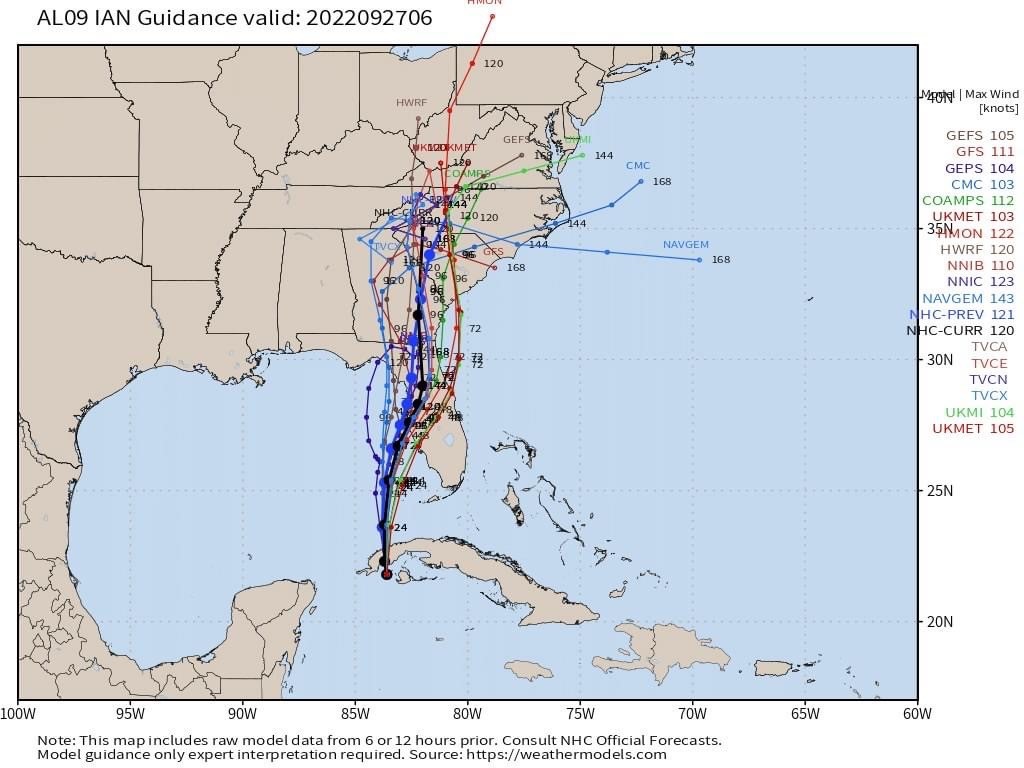

The trip to the Dry Tortugas required a favorable weather window, not only to get out to the remote site, but also to get back. The prevailing winds were from the east and north, so sailing there could be fairly easy but sailing back, beating our way into the wind and waves, could be a nightmare.

We had friends who got smacked down by a waterspout during a storm at the anchorage there, and we didn’t want to experience that firsthand. They were okay; they were able to turn the engine on and motor hard into the wind, avoiding being beached. Of the six boats anchored that night, three ended up on the sand.

Key West

As we waited for favorable weather, we survived more than four months in the Garrison Bight mooring field of Key West. It was a rough way to live; we were buffeted by north winds almost constantly, had infrequent pump outs, and often got soaking wet just crossing the mile of choppy water to the dinghy dock. Phil’s review of the location on Active Captain featured two stars:

Exposed and often uncomfortable

The mooring field is completely exposed to the prevailing winter winds from the north, which makes living on the ball often uncomfortable and sometimes unsafe in a north wind. Very windy and wavy. We were there for four months. I kept a spreadsheet and recorded that 1/3 of the days had small craft advisories. Dinghy travel to shore typically involves full foulies or a swimsuit since the salt spray is unavoidable. There was one fatality from a neighbor taking her dinghy to her boat while we were there. Pump out is supposed to be weekly, but could be delayed to two weeks or more due to weather. Very little communication from the marina office. The mooring balls have NO PENNANTS, making picking up the mooring ball difficult except in calm weather.

Despite the difficulties, we enjoyed Key West’s unique vibe, its “fabulous” restaurants and bars, and the chance to be locals. We changed our drivers’ licenses to a made-up Key West address, since the mooring field itself was not acceptable for that purpose. (We used the address of the dinghy dock.) We started asking for the local discount at the bars after a bartender at the Harry’s Hair of the Dog Saloon told us most places take 10% off for locals.

We climbed the Lighthouse, toured the Coast Guard ship and the Truman Little White House, marched in the locals parade before Fantasy Fest, and placed a few “Catmandu” stickers in our favorite bars. We ate and drank our way down Duval Street and then explored restaurants on the back streets and narrow walkways.

We found the best Italian place (Only Wood Pizzaria Trattoria down a brick-lined alleyway off Duval St.), the best Mexican (Old Town Mexican Café, open-air patio with a tree for a rooftop), best vegetarian (The Café, friendliest staff in town) and attended the Friday night sound checks at The Green Parrot. We bought the T-shirts.

Toward the end of our stay, we realized we were never going to get a good enough weather window to visit the Dry Tortugas. We decided to try again in another year, another season, sometime in the future. We had good reasons for not going.

We welcomed my son Anthony and his wife Maeghan for a February vacation, opting for a week at a dock instead of subjecting them to travel through the mooring field. (The week at the Key West Bight Marina was nearly $1,200.) We took them to the Brewery for lunch, and they presented me with a morse-coded gold bracelet. Phil whipped out his “decoder ring,” and it took two letters for me to start crying with joy: G-R. Grammy! They brought me a gift like no other: a grandchild on the way, my first.

When March came, it was time to move. We had spent all the fun chips Key West had to offer, and we were tired of the mooring field. We had other reasons for moving, and slowly, sadly, we were realizing our dream of a spring season in the Bahamas would have to wait.

Key West to Key Lois to Marathon

We set out for Marathon two days after dropping the “kids” at the bus station. We had just been sailing with them a few days earlier, so it was fast and easy to leave the dock. We followed our October course in reverse: out of Key West Bight, left to the channel, past the harborside resorts and bars, past Wisteria and Tank Islands, and into Hawk Channel.

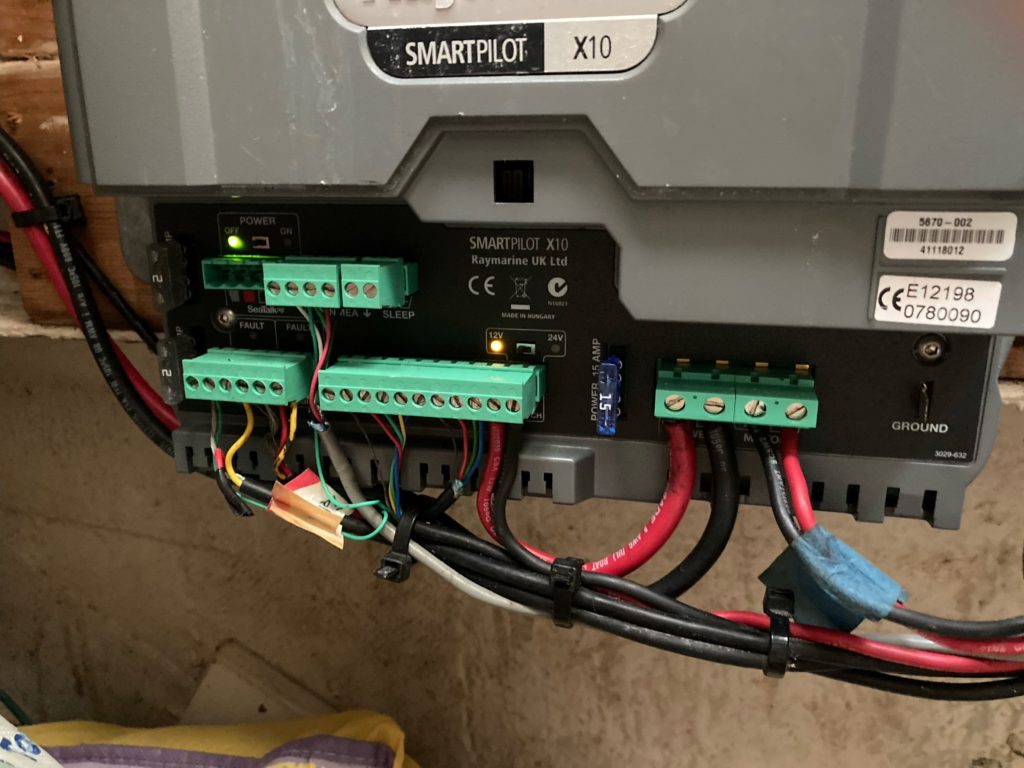

The winds were light from the ESE, so we motored the 21 miles to Lois Key. Along the way we kept our eyes out for wildlife and saw several Portuguese Man-of-Wars, the blue-tinged floating blobs you want to avoid while swimming. Although we were using the autopilot, we had to hand-steer around scores of annoying little crab-pots. At just after 1 pm, we saw Lois Key in the distance and at 1:45, we dropped anchor there in 10 feet of water.

The winds had died down to about one knot, and seas were calm. We saw one large turtle break the surface near the stern as we relaxed in the cockpit. He dove again a minute later. Just before sunset, four large dolphins appeared from the east and swam under the boat. They came up on the other side, close to the cockpit. We watched them as they swam off to the west together.

Sunset was little more than an orange-pink glow in the western sky, and when darkness fell, it was intense. There were so many bright stars, but the only man-made lights came from the keys to the northeast. We could still see a faint glow to the west from Key West, but it was still a very dark night. The next morning, we had coffee and breakfast bars at 7:30 and then tried to pull the anchor. The anchor windlass failed to turn on. “I guess it’s arm day on the boat again,” Phil said, and muscled the heavy chain and anchor onboard at 8:40.

The wind and waves were calm as we motored toward Marathon. The ocean was flat with tiny ripples that sounded like turtles breaking the surface, but when I looked, it was nothing but water. I was at the helm for most of the day, giving Phil a deserved rest. We recognized land features to our left, sailing by the Bahia Honda Bridge and then the Seven-Mile Bridge as we approached Marathon. Since there was a waitlist for the mooring field, we anchored along the west coast of Boot Key at around 1:45 in the afternoon.

The next day, we boarded a bus for Key West, retrieved our car and closed our PO box. On the way back, we got a call from the city marina – our mooring ball was ready: Romeo 8. It was easy to grab the pennant this time, and we settled in to our new home in Boot Key Harbor, near the entrance to Sister Creek. Ospreys and bald eagles were calling overhead, and later that afternoon, dolphins came to meet us.

I have already written my Love Song to Marathon, and Phil wrote a tribute to its many tiki bars. Nothing in the next six weeks changed my mind about this worthy cruisers’ destination. On the mooring balls, a community of helpful, friendly, concerned citizens take to the radio every morning at 9 and share the news of the day: upcoming activities, people coming and going, people needing help, and truly corny “Dad” jokes. We met friends at the Friday night happy hour that we will reconnect with, down the line. But this is a sailing blog, and by mid-April, it was time again to go sailing.

Other Reasons

To explain our reasons for moving, for not going to the Bahamas, and for heading north, I have to go back a few months. While we were hanging on to the mooring ball in Key West, I had a few medical tests done that I had put off for too long. One of these was a mammogram, followed by a biopsy. Here is an excerpt from my journal:

Feb. 1, 2024: I guess I will remember this date for as long as I live. It’s the last day I woke up without cancer.

The doctor called me and asked how I was, any soreness, swelling. Then she said, “The tests came back positive for malignancy. There are cancer cells in the breast and the lymph node.”

Pause. Breathe.

“It’s invasive ductal carcinoma and it’s metastatic,” she says quietly.

Phil is listening so I stay quiet while she tells me to pick up a CD of my images at the doctor’s office and make an appointment right away with an oncologist. She recommended Baptist Hospital Breast Cancer Center in Miami.

“Okay,” I said. “Is it treatable?” Then Phil got up and put his arm around me.

“Yes,” she said, and added, “I was pretty sure this would be the result. Sometimes I hate being right.”

Phil held me while I explained what she had said. I cried a little. I guess I’m allowed. I have metastatic breast cancer.

So, instead of planning a crossing of the Gulf Stream and a season in the Bahamas, we were planning a way to get closer to my oncologist, my future treatments, and an affordable dock where we can spend the hot hurricane season with air conditioning.

Some treatments were available at Fishermen’s Hospital in Marathon, so we headed for the mooring field there. Weekly treatments would start in mid-May in Miami, so we called our previous home, Loggerhead Marina in Hollywood, and asked about a slip.

“Your old slip will be available,” the manager said. “When will you be here?”

“Mid-April,” said Phil. It gave us six weeks in Marathon, where we could get some treatment, and it was closer to Miami, where we would be going for tests and appointments.

I am going to be a grandmother. Phil and I are sailing to the Bahamas next spring. Our plans have to be rewritten, in the sand, but these things will remain even after high tide.

We all have reasons for moving.