The fishermen know that the sea is dangerous and the storm terrible, but they have never found these dangers sufficient reason for remaining ashore.

– Vincent Van Gogh

When you walk through a storm, hold your head up high and don’t be afraid of the dark.

At the end of a storm, there’s a golden sky and the sweet silver song of a lark.

– “You’ll Never Walk Alone,” by Rogers and Hammerstein, Carousel

The storm was supposed to be called Hermine, but a swift upstart came racing off the coast of Africa behind it and took the name away to sea. So, then came Ian. It was a slow mover, keeping a steady pace across the Atlantic as Storm 9 until it finally earned a name as it reached the Caribbean. “Waiting for a hurricane is like being stalked by a turtle,” a friend posted on Facebook. We didn’t think Ian was coming for us.

The track was uncertain, but the tropical storm went south of Puerto Rico and made for the Western Caribbean. Like many others before it, Ian could gain strength in the warm waters of the Gulf and head toward the shoreline of Louisiana. Poor New Orleans! I really thought that’s where it would go. Local knowledge tells us that if a storm passes south of Puerto Rico, it won’t threaten southern Florida. Ominously, another storm in 2004 – named Charley – also passed south of Puerto Rico and did a lot of damage in southwestern Florida.

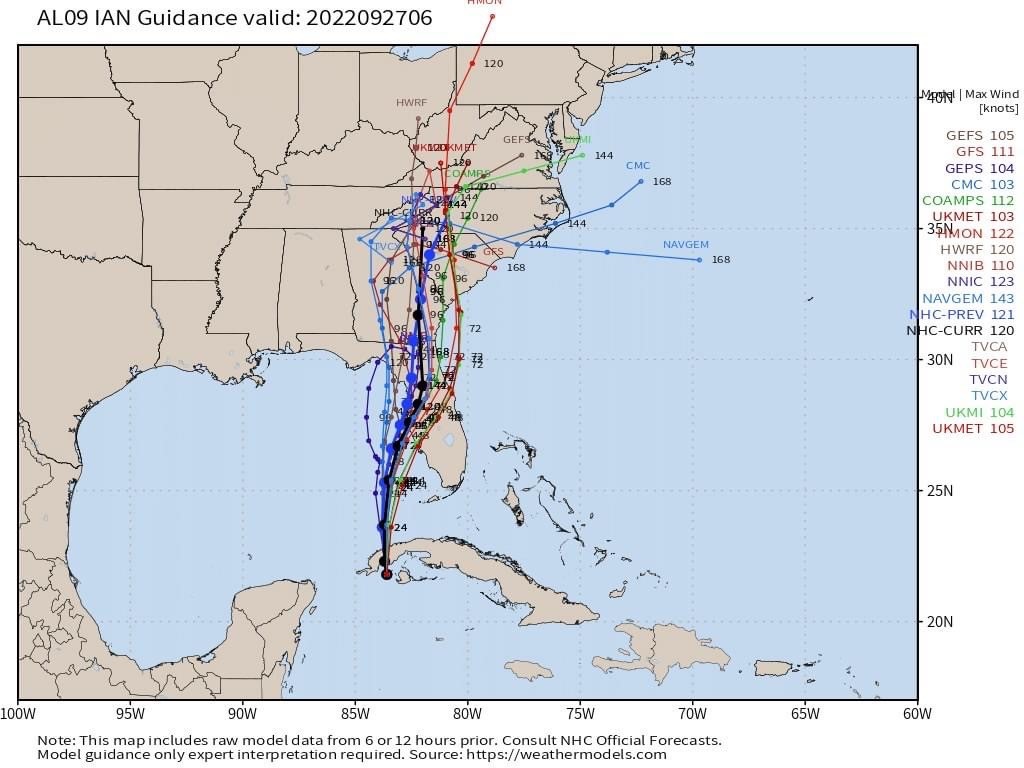

Friday, Sept. 23: The spaghetti models (those stringy looking storm track predictions) were promising a turn to the north across the island of Cuba and then an easterly turn toward the west coast of Florida. It wobbled to the west, giving us a little relief. But we were concerned about high winds and began preparations. The marina office told us we can move to a larger slip, to give the boat room to bob around. We made a list of high-wind preparations. Luckily, we had friends coming to visit who had lots of sailing experience and we listened carefully to their advice.

Saturday, Sept. 24: With our friends’ help, we removed the head sail and stowed it inside. Then we moved Catmandu to the larger slip, so the boat was now facing west. Since the storm would pass to our west, that seemed the most likely wind direction. This proved to be wrong, but the decision to move was definitely right.

We were able to double our lines, add more lines to the midship cleats, and put spring lines on both sides to keep the boat loosely in place. Too tight, the lines or cleats could break; too loose, we could bounce off the concrete dock or the wooden pilings. Phil went to WestMarine to buy new lines and found the stock was greatly diminished – no surprise. He came back with two new lines, shorter than we wanted, at a cost of $190.

Although we thought the storm would bring high wind and waves from the west, we didn’t base our preparations on that fact. We were looking at a long fetch in that direction, which means a great expanse of water loomed with no obstructions. Beyond the mouth of Boot Key Harbor, there is Hawk Channel with its shallow coral reef, and beyond that, nothing but Cuba to the south and a few islands to the west.

It is best to shelter from the fetch, and some sailboats in the harbor began to leave for the Shark and Little Shark Rivers, up around the south coast of Florida and into the Everglades. The eventual path of the storm put these boats closer to the eye, but they tucked into the mangroves and remained until Ian passed. They all made it with little to no damage. The natural protection of the narrow river and dense mangrove trees made this a nice hurricane hideout.

Sunday, Sept. 25: We watched the forecasts every three hours. On the day the storm was forecast to pass closest to us (Tuesday), there was a 20-30% chance of 34-knot winds, and a 5-10% chance of 50-knot winds. In our location, there were no hurricane watches or warnings because the wind has to be 65 knots or greater to be a hurricane (75 mph). (Phil has a way of explaining watches and warnings: Taco Watch – We have the ingredients for tacos. Taco Warning – We are having tacos.)

We were never advised by authorities that we should evacuate. At this point, we knew it would not be a direct hit. In fact, we were out of the cone altogether: No tacos. So we wrapped the main sail, lifted the dinghy from the water and secured the outboard on the back of the boat. We took everything that could fly and secured it inside. We left the dodger and bimini up, a decision we questioned later. (For non-sailors, these are the canvas coverings over the back of the boat.)

Then, Ian shifted slightly. Fed by warm ocean waters, it became larger and stronger. It moved closer.

Monday, Sept. 26: By Monday, the wind was making an eerie whirring sound above the marina, and small rain showers passed through. The rain bands from Ian were approaching, even though the eye was still 200 miles away. We spent the day getting ready: tying down the solar panels, securing the cockpit table, strapping in the dinghy. Ian was moving slowly across the tip of western Cuba.

At 6 p.m., the air conditioner stopped working. It wasn’t the storm at all, just a reminder that a boat will present problems no matter what else is going on. The inlet through-hull was clogged. As Phil tried to unplug it, the plumber’s snake broke. We headed to Home Depot. Phil bought a new snake and a little plastic drain cleaning tool ($3) that busted up the clog.

As soon as we got the AC running, I started closing the hatches. There was a scary sound of distant thunder. I was reaching up to close a hatch when we simultaneously saw a brilliant flash and heard a deafening crack. I ducked and screamed but was not hit. Phil and I looked at each other. “That was close,” I said.

“Right here,” he said. We found out later that lightning had hit the boatyard less than a quarter mile away and knocked out the Wi-Fi signal. (A week later, it still has not been repaired.) Lightning is a danger to boats with tall masts. Phil says he relies on the “buddy system,” which means positioning next to taller boats. The wind kicked up in the middle of the night and Phil went outside to loosen some of the lines and alleviate the banging. The boat was straining all the dock lines, but the wind was primarily from the southeast. The dinghy was swinging against the stern, making a lot of noise. Sleep was difficult.

Tuesday, Sept. 27: I confess to Phil that I am having trouble writing this blog. It should have been done days ago – and it’s getting so long.

“I know how it should start,” he said.

“How?”

“It was a dark and stormy night…”

It started with a tornado watch, and then a warning. We are having tacos. I’ve always wanted to see a waterspout, but only from a distance. Tornado warnings are scary, to be sure. At 9 am, the winds were only at 12 knots but it was dark and stormy. People were starting to come out on the docks, checking lines and making last minute adjustments. We loosened the lines on the dock side to give Catmandu room to move around without hitting. Rain came in small squalls all morning and the wind started to build. By afternoon, we could no longer get off the boat. We turned on the wind instrument and saw gusts of 28 knots. I took a picture of a palm tree. Looking at that, I can hardly imagine what 120 knots would look like.

Tuesday afternoon, we started rolling and heeling to the starboard side. The winds were roaring, and they made a flute-like sound going across the masts and shrouds in the marina. Outside, it was impossible to talk over the higher gusts, which were now in the upper 30s. The palm trees were all fanned out to one side. When the storm track shifted slightly to the east, it brought our location to the very edge of the tropical storm force winds. Farther up the west coast, Fort Myers was getting ready for a direct hit. Ian passed Key West and stirred up 25-foot waves in its wake.

Phil doubled the port stern line and backed it up by winding the end around the winch. The cat curled up under the table, a spot she claims whenever the boat moves around too much. By suppertime, we were rolling around so much, I had to release the gimble on the stove. This allows the stove to swing, keeping it level. We were tied to a cement dock, but bobbing around as if we were in open ocean.

The wind rattled the aluminum frame that holds the bimini, making the boat sound like it was coming apart. As evening fell, we looked at each other every time a sustained gust leaned the boat to 20 degrees or more. The winds were beating on the port stern, kicking us in the butt. The poor dinghy was swinging around like a balloon on a string.

Since the wi-fi was still out, we decided to watch a movie. I guess it was a strange choice, being on a boat in a storm, but we watched The Abyss on DVD. The winds were getting stronger outside, and we started getting periods of pelting rain. Phil put towels in the aft cabin where rain comes in to prevent wet pillows on the bed. But we weren’t sleeping. The boat was moving around so much, our Fitbits were registering steps. I was waiting for dock lines to snap and throw us against the pilings, or worse.

After the movie, we went outside with flashlights to check the lines, and all were holding despite the onslaught. We checked the wind speed and found sustained winds of 30 knots with occasional gusts up to 55, more than gale force. (We found out later that gusts of 67 knots had come through Boot Key Harbor. Hurricane force is 65.)

Looking out into the wild night, I imagine being a primitive human, with no knowledge of weather and no advance warning for storms. In that mindset, with this kind of fury, of course I would believe the gods were mad at us. There could be no other explanation.

Wednesday, Sept. 28: After a long night, we heard a lone voice on the VHF radio. “Okay,” he said, “I’ve had enough of this!” We could not pull the boat to the dock to get off, the wind was still so strong. Phil hooked a dock line to one of our winches and used that to pull the boat close enough for him to jump to the dock. I wasn’t going to try it. He took a picture of the boat, noting the weird color of the water. It looked like pale blue milk. It was so full of sand and silt it had become opaque.

Elsewhere, Ian was churning toward the west coast of Florida and gaining strength. The Waffle Houses closed – a Florida signal that something terrible was coming. We were starting to relax a little and felt renewed sympathy for those in the path of the storm. We had made it, but not without damage. The solar panels had somehow rotated to an unnatural position, and at first we couldn’t figure out how that happened with the outboard motor in the way. Then Phil discovered the dinghy davits (the stainless steel racks that hold the inflatable boat up) were bent. Yes, the winds had bent steel.

Aftermath: I love storms. I love watching lightning in distant rain clouds, especially over the water. A gentle wind can stir up emotions and memories along with the rustling of the palms. I’m the last one to take shelter when the first drops of rain fall. Now that this storm has passed, even after witnessing the fury of the wind, I don’t love storms any less. I will still marvel at thunderheads, feel the thrill of lightning strikes reflected in the ocean, still watch the horizon for waterspouts. But I will think twice about being on a sailboat within two hundred miles of a hurricane.

loved reading this. i felt like i was there. and u both are nuts!