“The great courageous act that we must all do, is to have the courage to step out of our history and past so that we can live our dreams.”

Oprah Winfrey

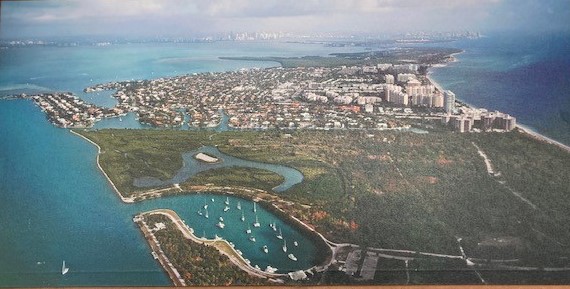

We lived on our sailboat in Loggerhead Marina for nearly three years. We got used to boat life: endless dishes to hand wash, trips to the local laundromat, walks up and down the dock with a rolling cart because the groceries or boat parts were just too heavy. We met wonderful, interesting friends who are nomads and disappear sometimes in the early morning on their way east to the islands or north to other ports. That is our story now. People will walk down Dock 500 and say, “Remember that couple with the cats? I wonder where they went.”

We are moving on, first to the southwest to explore the Florida Keys and then on to Dry Tortugas; perhaps we’ll turn east to the Bahamas or up the west coast of Florida. It’s time to start our cruising journey. First, we have a list of boat projects to do, and an engine to refurbish. Six more months of marina life, and then we’ll be moving – probably. But this edition is dedicated to life on the dock.

Marina life attracts mostly couples and single or divorced men. The live-aboard community doesn’t include many single women, but I think that may be changing. It’s an inexpensive way to live, especially if you can find a boat you can afford that provides a comfortable way to sleep, eat, and shower.

Our 1998 Catalina 380 was less than $90,000, fully equipped and ready to go. We didn’t want a project boat since Phil and I were still working. Dockage can be expensive and hard to find, but for our size boat, it ranges between $900 and $1300 a month. That includes water, electricity and pumpout services. (If you’re looking for a dock, it is helpful if you say you would like to “stay aboard” instead of “live aboard.” Some marinas frown on the latter.)

Marina life has some down sides. Boats don’t normally have washers and dryers, so a visit to the local laundromat is a recurring treat. Most marinas have a laundry room for the boaters, but often the dryers don’t work or are so busy you can’t get a machine. Another inconvenience is the pumpout service. It is not easy to get on the list for some reason, and a regular emptying of the boat’s waste tank is essential.

There are other things that some people wouldn’t like. Your neighbors are very close, like 10 to 15 feet away. If they are good neighbors, that’s fine. If they have barky dogs or loud music you hate, it’s not. We have been fortunate to have great neighbors for the past few years, so we have no complaints. We made good friends at our last marina, and became part of a community that we really enjoyed.

And that’s where the joys of marina life come in. Boat people are a breed apart. At the risk of generalizing and stereotyping, I’d say people who live on boats are interesting, courageous, fun-loving people. Our dock had lawyers, real estate brokers, doctors, and business owners in various stages of work/retirement. Some sold boats for a living, one was a working chef, one owned a solar panel business, and one was a bronze star recipient. Then there were the entrepreneurs who took any project for pay, started and lost ventures, and got along however they could. They are the most interesting.

Just like a small town, there was gossip, tragedy, love stories, and scandal – and everybody knew. One neighbor with a heart problem (and a ferocious dog named Marco) called 911 when he had chest pains, and the dog kept the paramedics from boarding his boat. I’m sure the poor dog was protecting his master, but the man died before animal control showed up to remove the dog. People talked about that death for months. Another man we knew fell from his boat, hit the dock with his head and never fully recovered. In fact, that story repeated often with varying tragic results.

Our cat Max was popular on Dock 500. He discovered he could leap from the boat to the dock and did it often. He was also smart enough to know which boat people would offer him a bit of deli meat if he visited. After he passed away, the neighbors started telling me how much they would miss him. I had no idea how many boats that cat had visited until he died. (He was old; he passed from natural causes.) “I’m going to miss that cat,” one neighbor told us. “He used to jump on board, find me, and tap me on the shoulder for a treat.”

People on the dock were always willing to help grab a line, walk a dog, provide a bottle of spirits or a takeout meal for dockmates in need. We tried to do the same, leaving flowers and wine on one boat for a captain whose husband was in the hospital for ages. People brought us gifts from their travels (delicious Wisconsin cheese curds), and one neighbor cooked us Creole tofu when he found out we were vegetarians. We cared for each other; we were family.

As one who has moved around all her life, it’s not easy for me to find a sense of community. My birth family was a military family, and we moved every two or three years. I attended three different elementary schools. It is hard to put down roots when they get torn up the next year or the next. So I loved marina life, and even though I might have been shy about making friends, I will miss Dock 500 at Loggerhead. I appreciated the feeling of belonging, and I crave that now.

We had been to our current marina several years ago on our previous boat and visited friends who lived here on two occasions. It has many of the amenities that we look for in a marina: a great swimming pool, a tiki bar, an exercise room, and laundry machines that work. It also has neighbors, and we have met a few. The wider community includes another marina and all the boats attached to mooring balls in Boot Key Harbor. They talk together on the radio every morning at 9 a.m. on the “Cruisers Net.”

Maybe saying goodbye is the curse of the nomad, and if I find that painful at times, I know I did it to myself. I embrace marina life, and I know (with any luck) we’ll be sailing away one day. I hope, in the meantime, that there is a place for us here: a community, a family, a home.

You and Phil are in my prayers while going through this hiccup in tour plans. My love to you both.