The turtle lives ‘twixt plated decks

Which practically conceal its sex.

I think it clever of the turtle

In such a fix to be so fertile.– Ogden Nash, “The Turtle”

Our latest outing into the waters around Boot Key took us farther south and west than we had ever been on Catmandu. We left the dock without a clear destination in mind, thinking we would sail west and visit one of two or three anchorages that had been recommended by friends. The original plan was to anchor between the old and new bridges at Bahia Honda, but currents are known to be strong there and we didn’t want to find ourselves pinned against a bridge in the middle of the night if our anchor dragged.

Other suggestions were farther away, and since the wind was so light (4 or 5 kts), we would have to motor all the way back, even if we managed to sail there slowly. So, we backed out of the slip on a fair Friday morning with the idea of sailing around just for fun and anchoring right outside our home harbor. It would give me some practice sailing and anchoring, which we will need for our future expeditions. (Phil doesn’t need practice, but as he puts it, “we are a team.” Winning teams practice.)

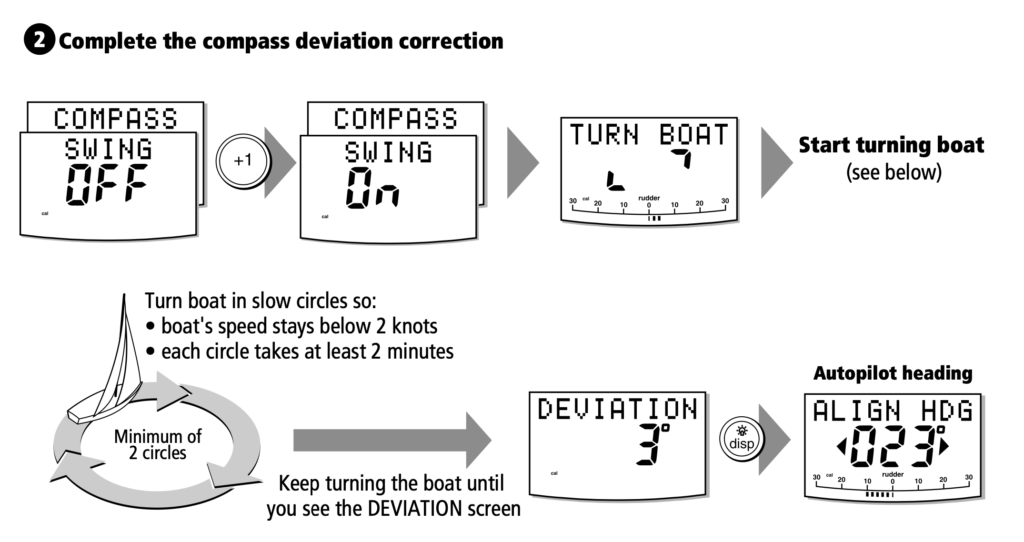

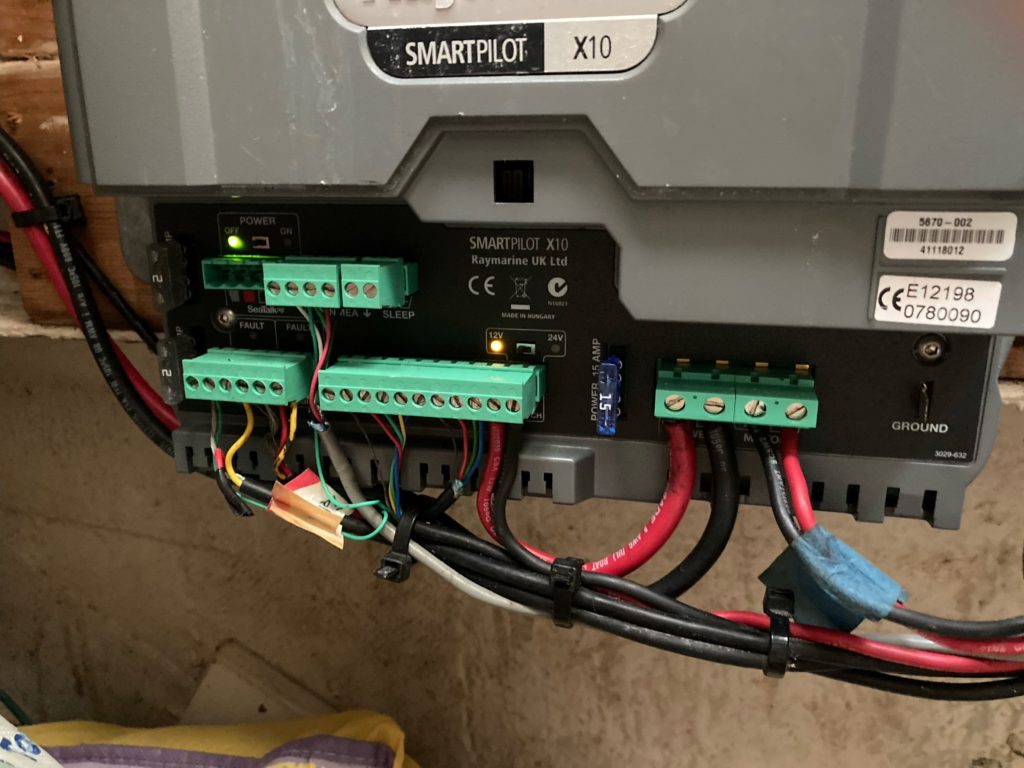

Phil drove out of the channel while I stowed the fenders. As soon as we cleared the markers, Phil went forward to hoist the mainsail. The wind was light and variable, mostly from the east and southeast. I drove in a crooked line, trying to keep the bow into the wind for Phil. After that, we let Otto drive (he seemed to work better than I did). I helped pull out the jib, noting that I forgot to put a stopper knot in the jib sheet (again). Soon we were sailing slowly toward the west, and we cut the engine.

What a difference it makes when the engine goes off. Every sailor loves that moment, when the diesel engine quiets and the wind takes over. We sailed a parallel course to the 7-Mile Bridge and passed the western end. We approached Bahia Honda, headed a little to the south, and kept going. The ocean was nearly flat, and it was a peaceful few hours.

We heard splashes all around us, and saw rings of white foam on the surface of the water. Phil figured out that they were made by turtles, and called them “turtle pops.” Sometimes we caught a glimpse of a turtle’s head, if it stayed up long enough, and sometimes a flipper would fly out. Most of the time they were too fast to see, and all we got was the ring of white foam and a splash. But they were all around us or possibly swimming with us. “We are beset by turtles,” Phil announced.

From the rare parts I could see, we think they were Hawksbill turtles, with a possible Loggerhead or two. The Hawksbill turtles have a distinctive spot pattern on their front flippers, and that is what I used to identify them. Turtles do not stay on the surface for long, and they are pretty quick to dive if they spot a human or a boat. Here is a Hawksbill turtle. They are about three feet long from head to tail.

We sailed for a few hours and then turned toward home. The wind was so light, it would have taken us several hours to get to the anchorage, so we had to motor sail. There were only three other boats there, so we had no problem picking out a spot. I drove while Phil dropped the anchor. He had to adjust the clutch on the anchor windlass, so I’m glad he didn’t send me forward to drop the anchor. I do have to practice that at some point.

We knew not to get too close to shore. In light winds, the bugs (no-see-ums) can be brutal. We had some adult beverages, listened to music and watched our old cat Maggie climb the companionway stairs and join us in the cockpit. She rarely comes outside, so it was good to see her making the effort. She took a walk around the deck and settled down beside us. In the distance, we could see a sailboat levitating over the water. Or, atmospheric conditions make it look like that.

Memorial for Mom

A few months after my mother died, the people at Seasons Hospice who cared for her during her last days gave my sisters and me a memorial lantern. We hadn’t planned a time or place to deploy it, and my sisters expected that I would light it and release it somewhere over the ocean. Phil thought it would be a good time and place to finally send it off. After grilling Impossible® burgers for dinner, we waited in the cockpit for the sun to go down.

My mother and father had a running argument about where to vacation. My dad wanted to go to the woods, and he usually won. But Mom loved the beach. She grew up in Westerly, Rhode Island and her grandfather had a beach house on Misquamicut Beach. She spent her summers there until she was 10, when the Hurricane of ’38 blew the beach house away. It also killed nearly 300 people in Rhode Island that day, including some of my mother’s schoolmates.

There was little left of the house on the beach, just a tiny bit of the cement sea wall. The top floor ended up two miles inland, the bedspreads still dry and folded on the beds. The hurricane did not dampen her desire to spend time at the beach. (It was different for her grandfather. Devastated, he sold the property without ever going back.) When my sisters and I would visit the beach with my mom, we would find that bit of sea wall and lay our towels out beside it.

This made me feel that flying that magical lantern over the ocean would be a fitting way to honor my mother. My sisters live far away, so they would not be able to participate. Phil and I got out the paper lantern kit, and making sure it was environmentally safe and ocean-friendly, we looked for the instructions to light it. Hilarity ensued. Apparently, AI has not advanced sufficiently to translate Chinese into understandable English. Wishing Light Operating Instructions (I am not making this up.):

- After the distribution of fuel to packaging equipment Kong Cross wire in the side of the field again deduction presses the fuel pressure lock firmly.

- A person wishing light take up a Top; another person fuel ignited the four angle.

After cracking up at this bit of nonsense, we figured out how to attach the fuel tile to the wire at the bottom of the lantern, and just after sunset at the anchorage, we tried several times to light it. It was old; it had been on the boat for almost two years, and it just would not light easily. It finally ignited, and we held it up off the deck, fire extinguisher at the ready.

When the “four angle” (the fuel tile was a square) was fully engulfed, the top of the lantern expanded to its full height and started to float away. I’m sorry I don’t have pictures, but it took both of us to hold the lantern and light it safely. I said, “I miss you, Mom,” and Phil let it go into the fading twilight.

We watched it float off the boat for about ten feet and then sink into the sea. We both started laughing, and I knew if my mom were looking on, she would be laughing too. The next day, as we were making our way back to the west to calibrate Otto again, I thought I saw the remnants of our memorial Wishing Light, disintegrating into the ocean as it was meant to do.

***

How does one tie up a blog with so many threads? I try to make each piece a complete tale, wrapping up all the facets in a well-constructed bundle with some kind of conclusion to make it all work, but this one is about a herd of turtles, my mom, and an overnight outing with Phil on our sailboat. A writing friend of mine asked me once if I consciously looked for a common thread to tie the blog together, and I said, “yes, I keep writing until I find it.” But the only thing I can think of to tie this one together is the ocean.

We live on it, my mother loved visiting it, and turtles pop out of it.

“I have been feeling very clearheaded lately and what I want to write about today is the sea. … It is my favorite thing, I think, that I have ever seen. Sometimes I catch myself staring at it and forget my duties. It seems big enough to contain everything anyone could ever feel.”

― Anthony Doerr, All the Light We Cannot See

You and Phil are in my prayers while going through this hiccup in tour plans. My love to you both.