I shared this insight with some other boat owners, and they all agreed that, definitely, putting your boat into the water is asking for trouble.

— Dave Barry

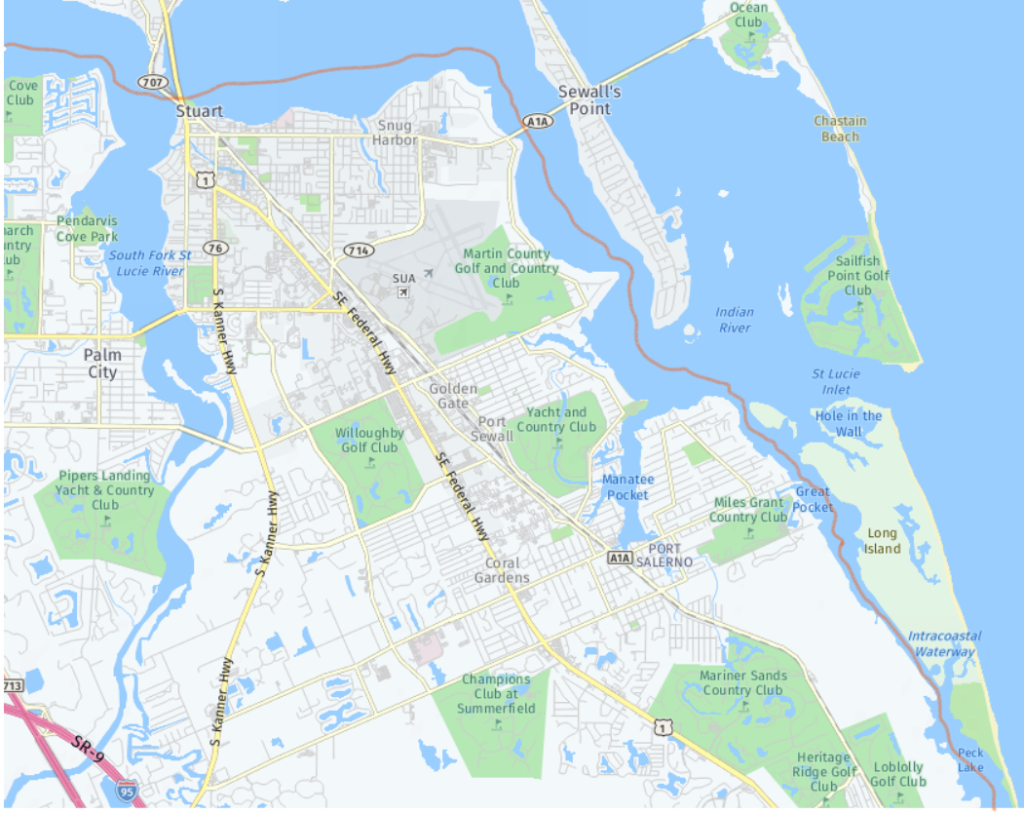

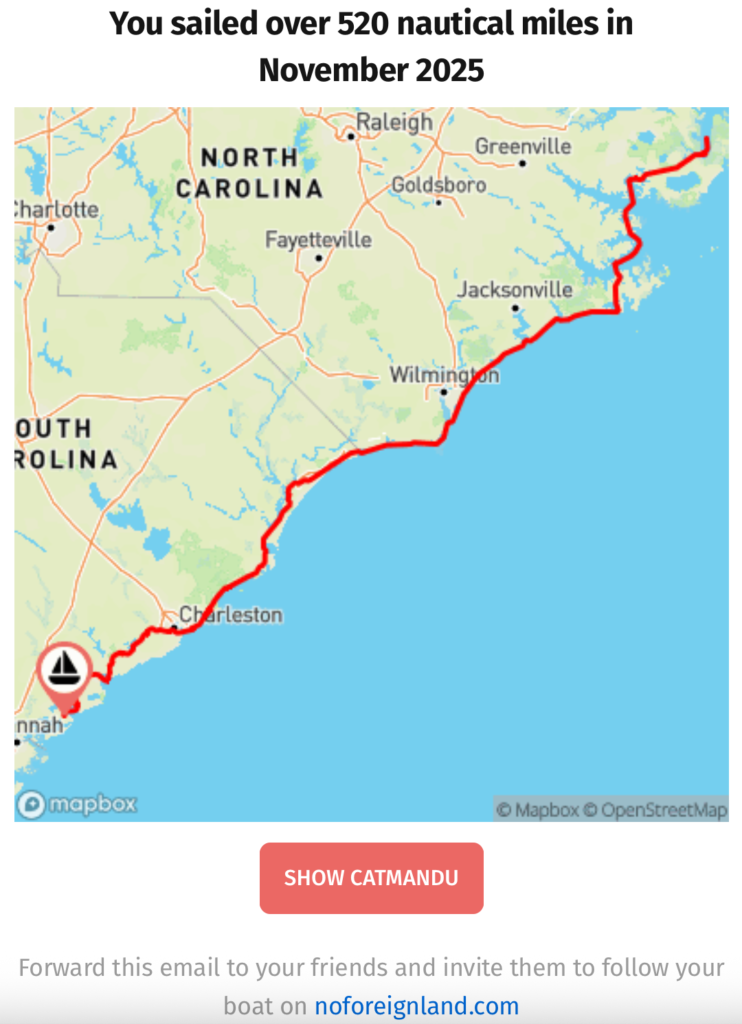

Catmandu does not have an engine anymore. The 27 year-old diesel engine on our Catalina 380 monohull sailboat is gone. After motoring and motor-sailing for several weeks south from Annapolis on the Atlantic Intracoastal Waterway, Kay and I are stuck at a marina only halfway on our thousand-mile plus journey from Annapolis to South Florida.

The last several weeks of our journey have had their share of not-so-great surprises (warships, murder barges, and cold weather), and some great surprises (bald eagles, fall colors, and dolphin sightings almost every day). Traveling the same stretch of water a second time this year brings a familiarity and comfort that makes the journey more fun. Since we have been keeping a daily cruising log, we can easily recall where we went before and avoid the marinas and anchorages that were not five-star stops. We can also revisit the five-star stops and try out some new marinas and anchorages. Finding new places is also fun.

When I was a young engineer working for Westinghouse in the nuclear industry in the 1980s, I learned the importance of backup systems and avoiding a single point of failure. For example, our sailboat batteries can be charged by shore power, the engine, and solar panels independently. A sailboat always has both sails and an engine, to be sure. On the ICW, however, one can seldom sail in the narrow, winding channels. That means there is no replacement for the engine, which is a single point of failure.

Our Westerbeke 42B Four was slow to start as we were leaving Annapolis in late October. It was in the 40s Fahrenheit. The engine would crank for a half a minute or more before turning over. This had never happened in our six years of ownership, but we had never operated the engine in such cold weather. I just chalked it up to the cold, and went onward. Maryland, Virginia, North Carolina, and then South Carolina. The hesitation became worse and worse with each passing day, but the engine always started eventually.

At Hilton Head Island, South Carolina, we took a slip at Safe Harbor Skull Creek Marina, as we had in July on our way north. We intended to stay for only one night. However, the next morning, the engine simply would … not … start.

Diesel engines are “simple” in that they need only air, fuel, and compression to run. I went through the entire troubleshooting charts from the engine operator’s manual and Nigel Calder’s Marine Diesel Engines reference book. I checked the fuel cut-off lever, changed the fuel filters, checked for blockage in the air intake manifold, opened the fuel tank to check for water and debris, removed and inspected the fuel pick up tube, tested the glow plugs, and checked the fuel lift pump. No joy. As Nigel Calder says, if you have done all of these things and the engine still does not start, “it is time to feel nervous and check the bank balance.“1

We called in a mechanic, and days later a man looking and talking like Nick Offerman showed up at Catmandu. He went through the whole system and found that — even without a compression test — the engine had little compression and there was significant piston blow-by. Internal combustion engines work by the principle of suck, squeeze, bang, blow. Air and fuel are sucked into the cylinders, they are squeezed by pistons, they are ignited with a bang, and then the exhaust gases are blown out. “Honey, we are out of squeeze,” I told Kay.

The mechanic said the piston rings are probably bad. The rings maintain compression in the top of the cylinders and keep the oil in the crankcase below. If the rings are bad, there is no compression and the engine will not start. New rings are not terribly expensive, but the bad news is that replacing them requires taking the whole engine out of the boat and disassembling it to be able to remove the pistons and the rings.

Our mechanic and his helper unbolted the engine and hoisted it to the dock under the boom (dot com) and took it to their shop. Not only were the rings bad, but the cylinder walls were scored and worn, pistons had erosion, the cam shaft had a worn lobe, and the crank shaft had deep scoring at the oil seal. Mr. Offerman (not his real name) kindly did the research but found that not all of the necessary replacement parts could be sourced. It was time to buy a new engine.

Westerbeke no longer makes engines for the domestic market. What kind of engine will Phil and Kay get? When will it arrive? How will it be installed? When can Phil and Kay resume their journey “home,” wherever that is? Stay tuned for our next episode.

- Calder, Nigel, “Marine Diesel Engines, Third Edition,” McGraw-Hill 2007, p. 105. ↩︎